Marion Kalter

Photographs

Arles, Ted Joans and the Beats

Marion Kalter’s

Long Summer of Photography

Text by Florian Ebner

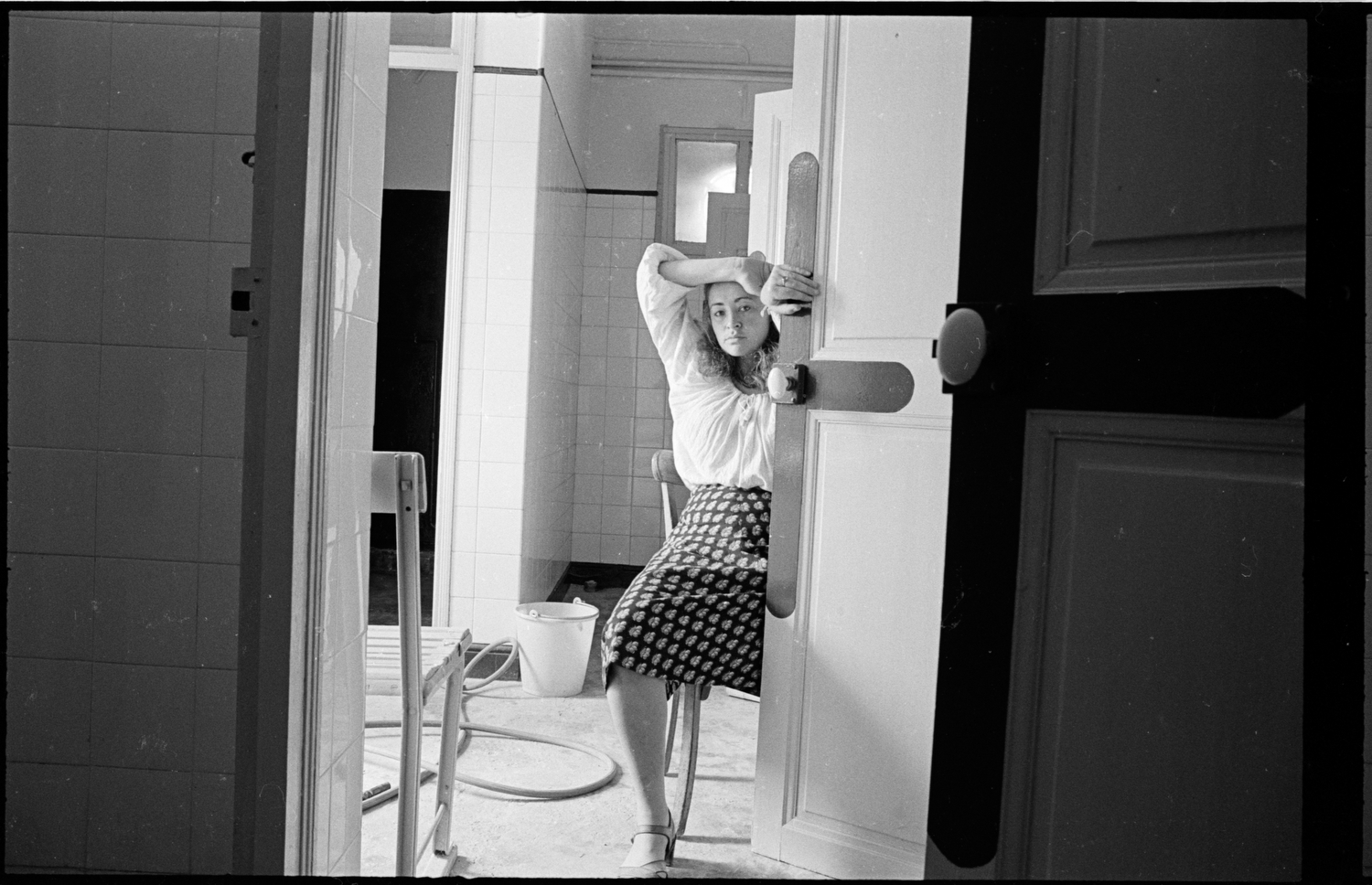

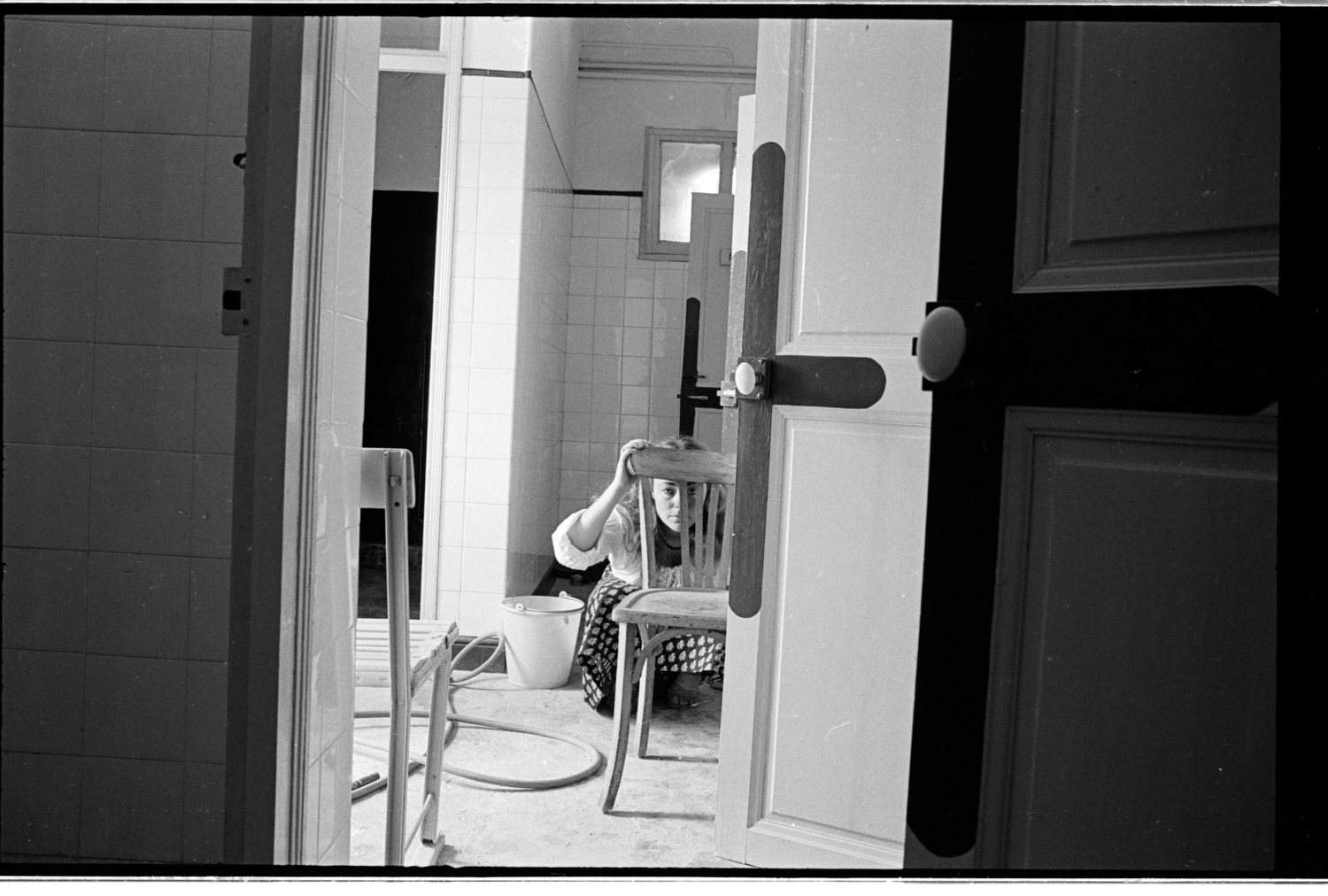

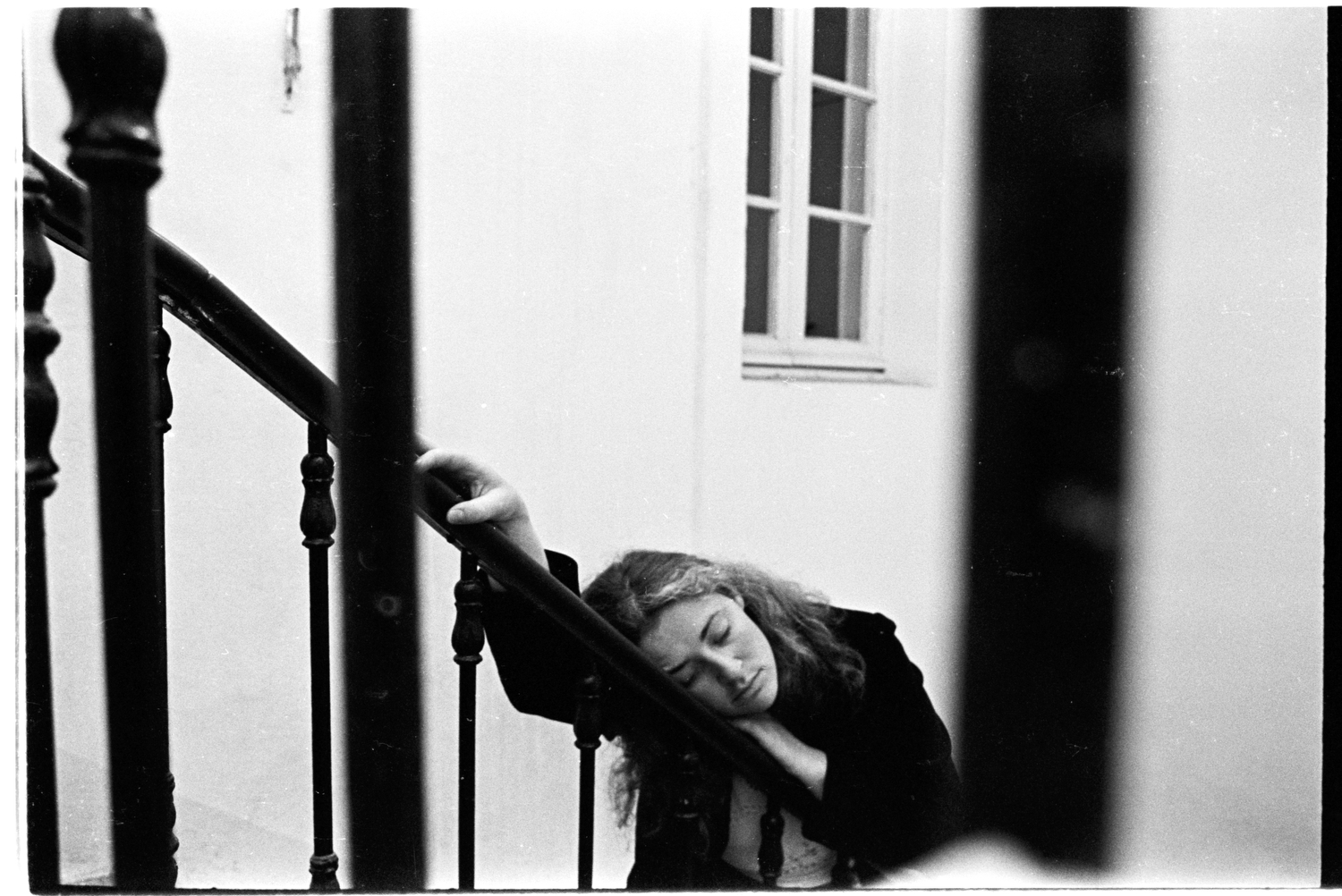

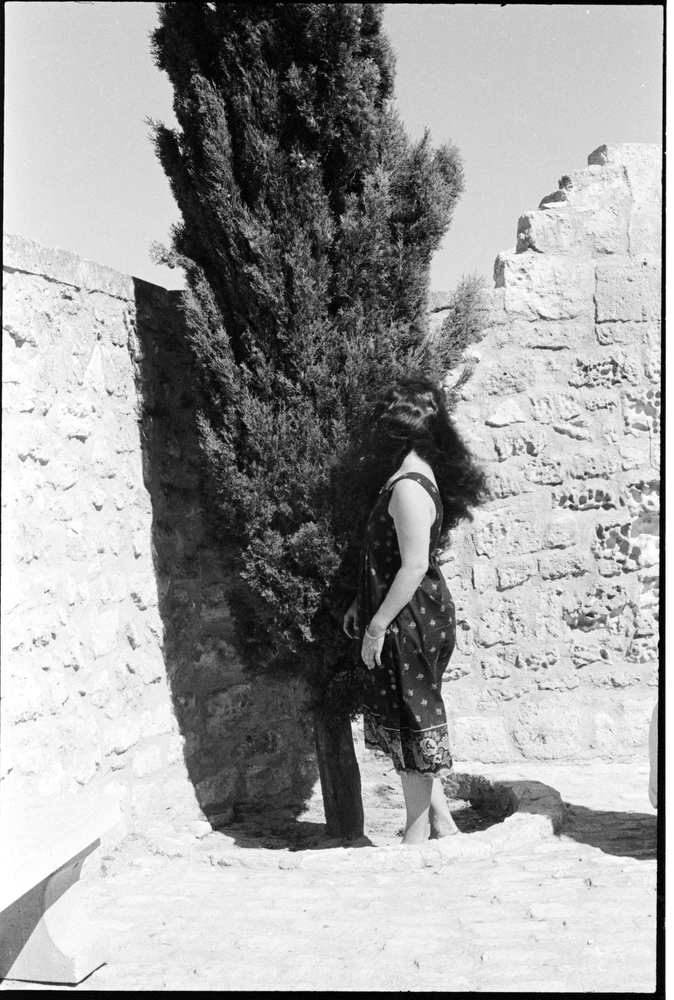

— Arles, 1976: A young woman, age twenty-five, once a fine arts student, poses for the camera (p.56). All but of the two of the sequence’s selected motifs feature a seemingly empty interior. She is always wearing the same clothes: a white, off-the-shoulder blouse and a flowered skirt. A chair helps her to take a wide variety of poses — clasped hands resting in her lap; her body turning away from the camera, toward the window; one hand clinging to a door and the other clapped to her forehead; or even cowering behind the chair, looking at the camera through the bars on the chairback. Other pictures show her sitting on the ground, almost as if immersed in a dream, her eyes closed, arms and legs swaying in a slight blur. The doors play an important role; they stand open, giving structure to the pictorial space and conveying an impression of being unlived-in, as if this were an empty factory or a decommissioned school. In two photographs the young woman comes closer: this time she has the device in her hand and photographs herself in an old mirror in front of a white-tiled wall. As a kind of mise en abyme, the two mirror images are definitely a paradigm for a moment of self-examination. Is it the slightly clichéd quest for a role in life, or are these staged attempts to approach herself or to put herself at arm’s length merely exercises in photographic style, on a search for a good image?

Forty-five years later the woman in the photographs, Marion Kalter, says that the solo photo session in front of the camera was inspired by a discussion with the Magnum photographer David Hurn. Elsewhere, she recalls the film Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), which was released in theaters that same year and whose director, Chantal Akerman, she photographed in front of a poster for her film (p.119). As should be expected, Kalter is someone who understands the camera as an instrument of free expression, not only as regards the roles assigned to people in society, but also in opposition to the tight corset constricting art and painting in those years. Like so many other women artists in 1970s, Kalter also drew upon this apparatus.

While navigating through the images selected for this show, I inevitably think about the title of a book. Der

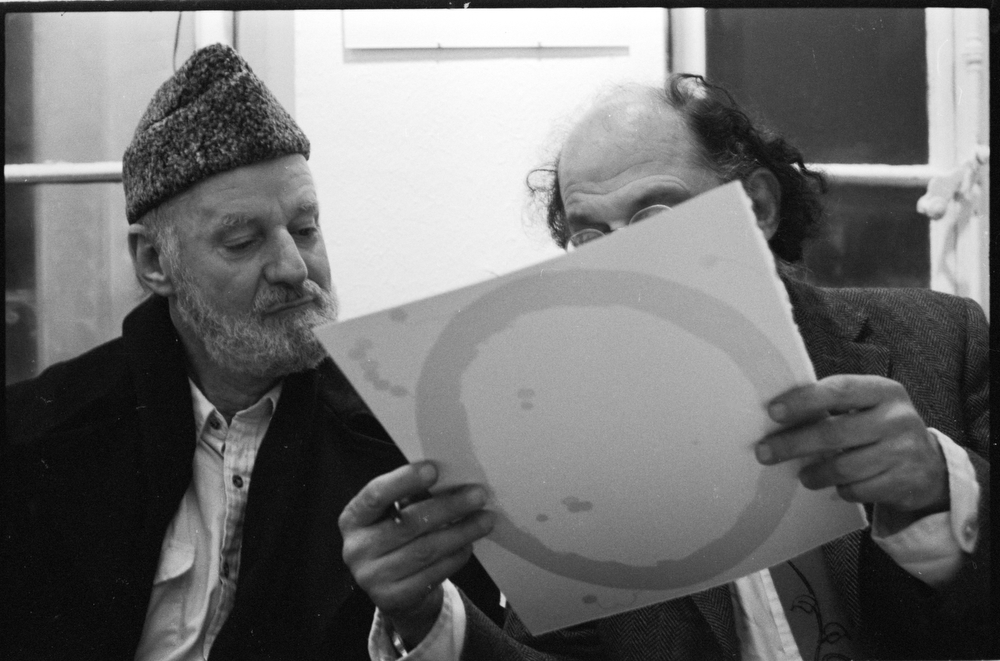

lange Sommer der Theorie (literally, “the long summer of theory,” but translated into English as The Summer of Theory) is the name of a treatise by the historian Philipp Felsch on the history of the reception of the (mostly) French structuralist and post-structuralist philosophy and theory in Germany, as told through the history of the Merve publishing house 1 in Berlin. It is not only the French intellectuals in Kalter’s photographs (Roland Barthes and Claude Lévi-Strauss) who triggered this idea

but also the many kinds of summer that can be discovered in Kalter’s pictures, which form the starting point for the question of whether there is also a “summer of photography.” If so, when does this summer begin, and when does it start for Marion Kalter?

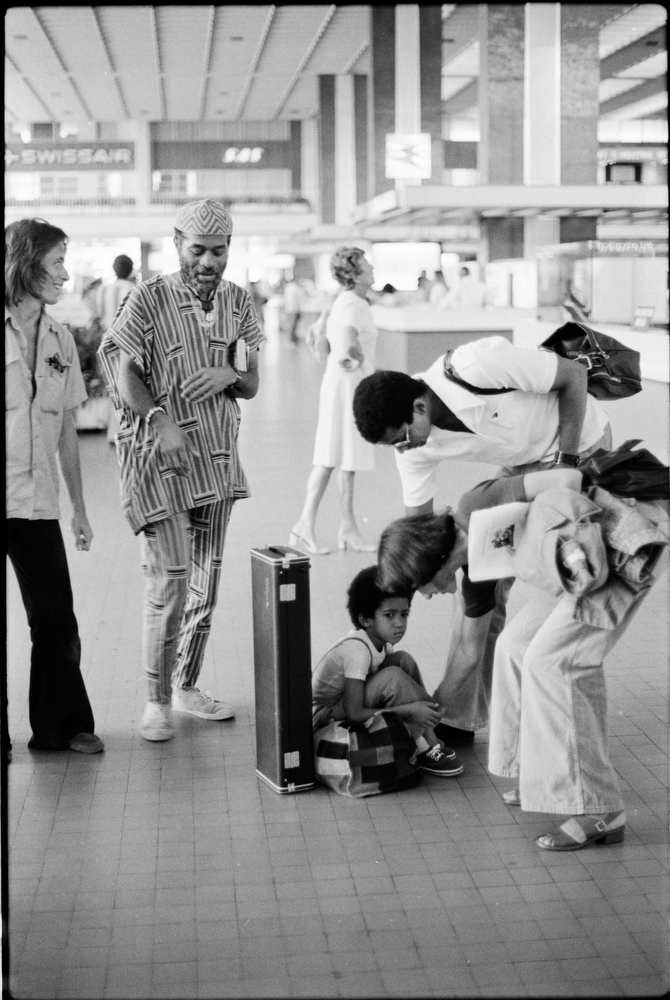

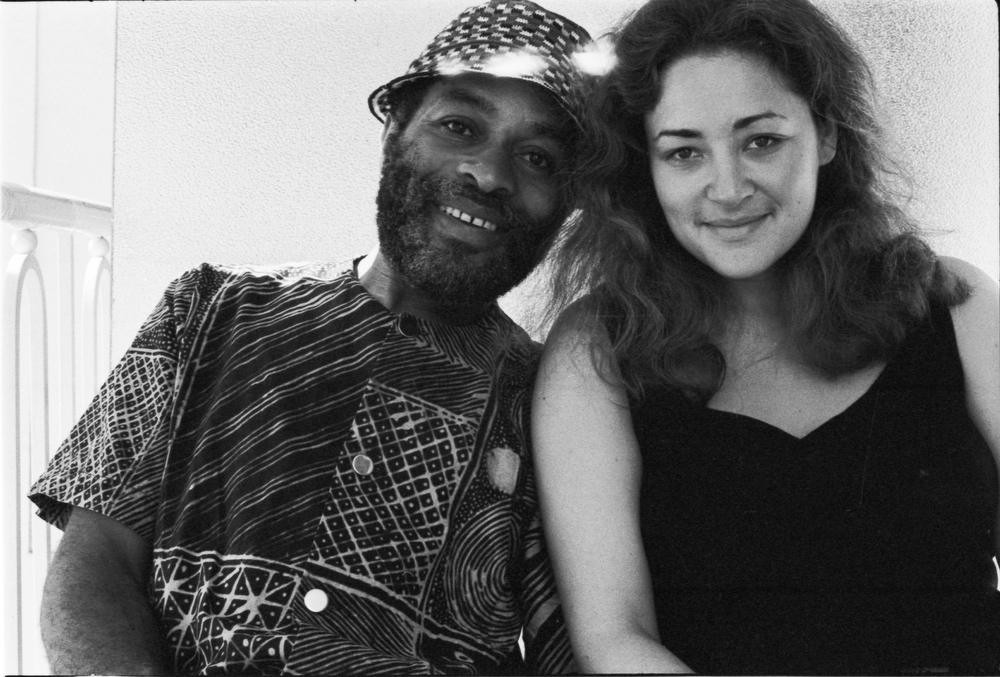

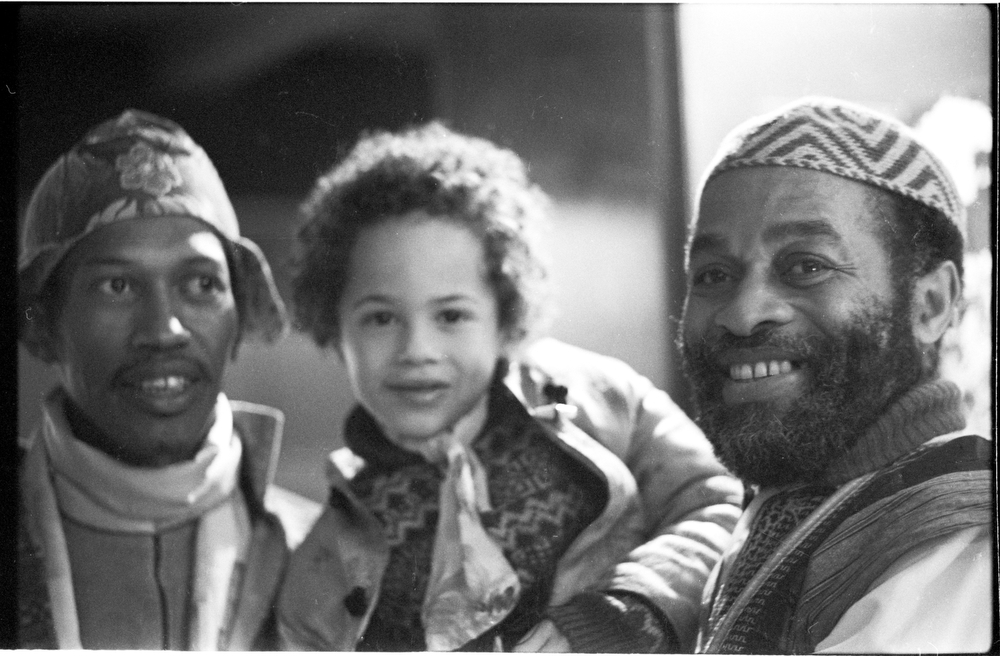

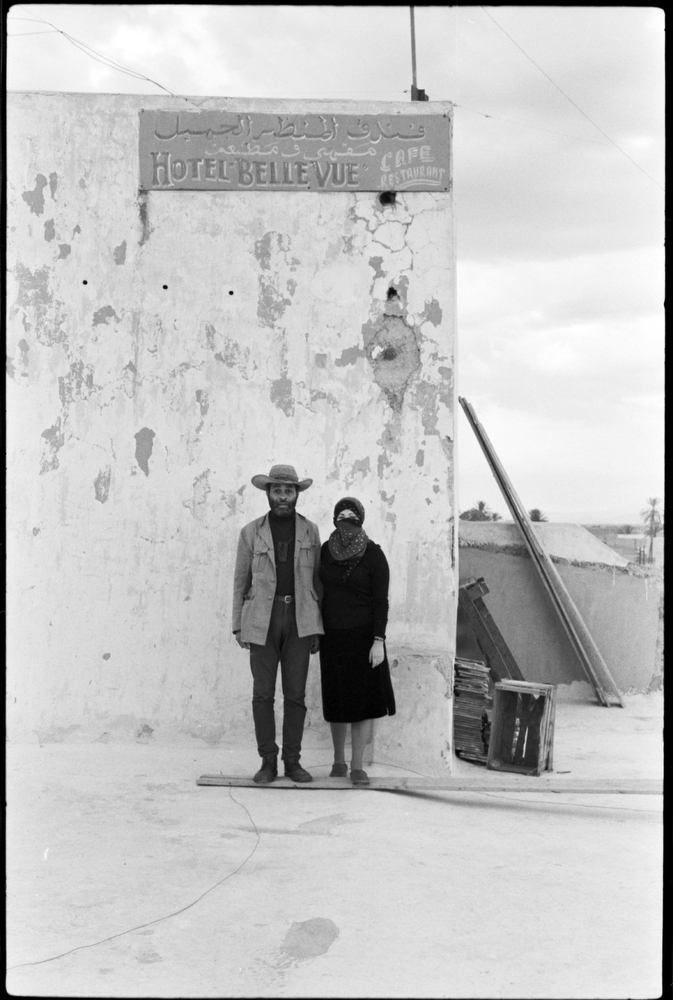

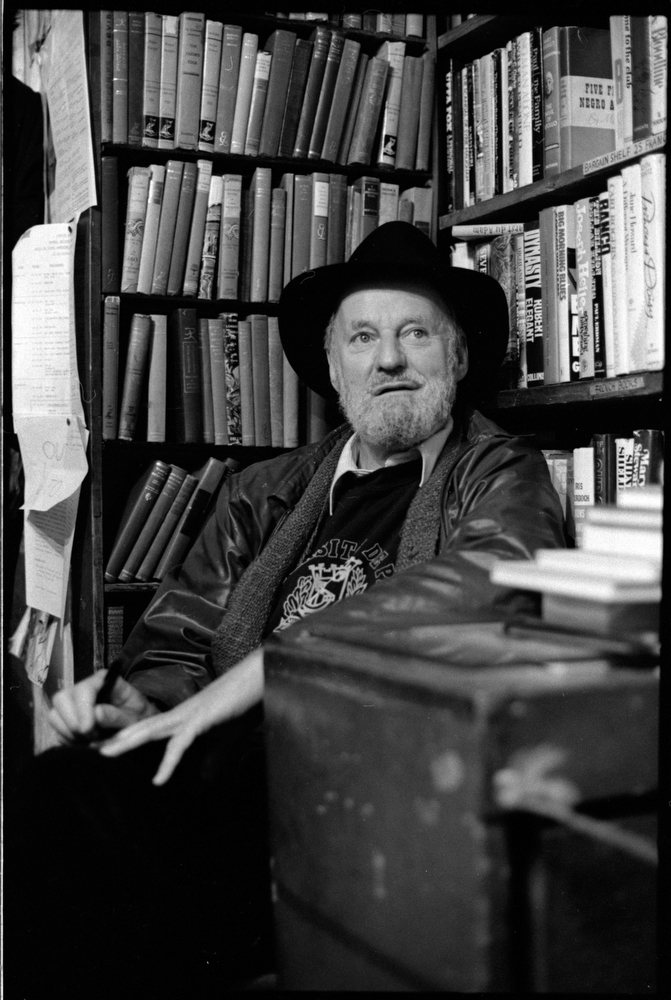

Of course, there are the first warm days when the eight year-old Marion experimented with a camera during a stay one summer with an English family on the Channel Island of Jersey (p.158), or the twenty-three-year old student, nude on the family sofa in one photo and clothed in another (p.164). Perhaps the real summer began in 1974, when she met the beatnik jazz musician and poet Ted Joans and began what she called her “Teducation.”

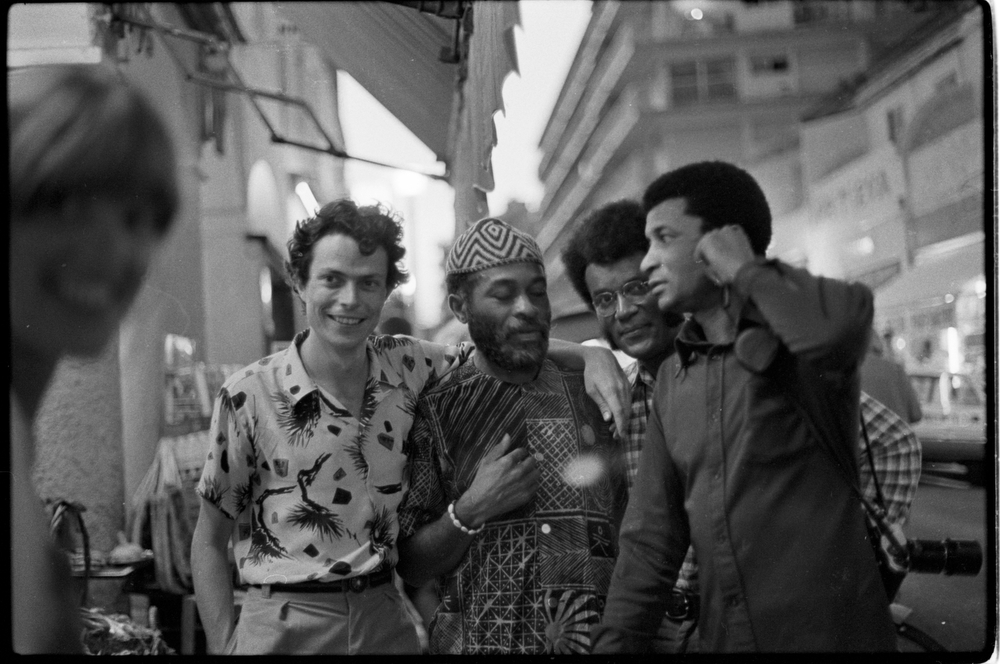

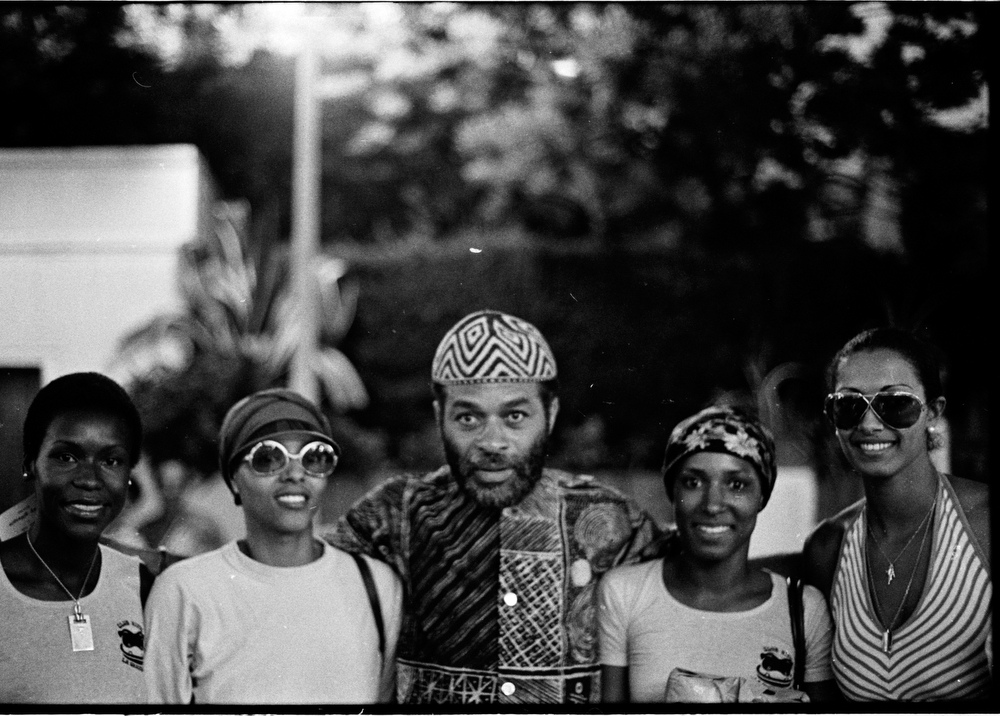

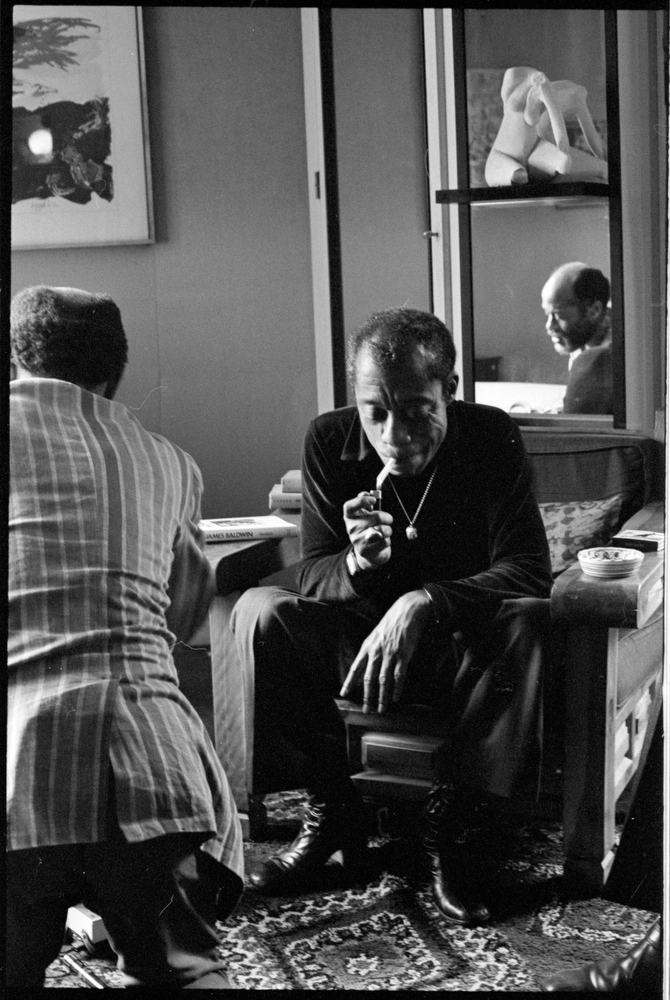

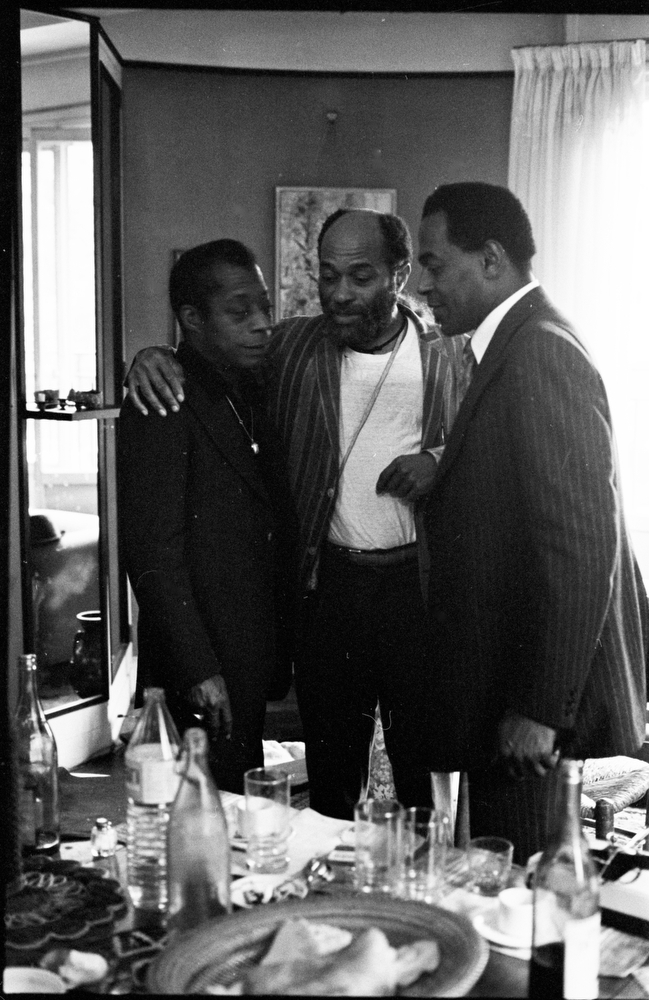

Joans, who was twenty-three years her elder, introduced his companion to a world that represented

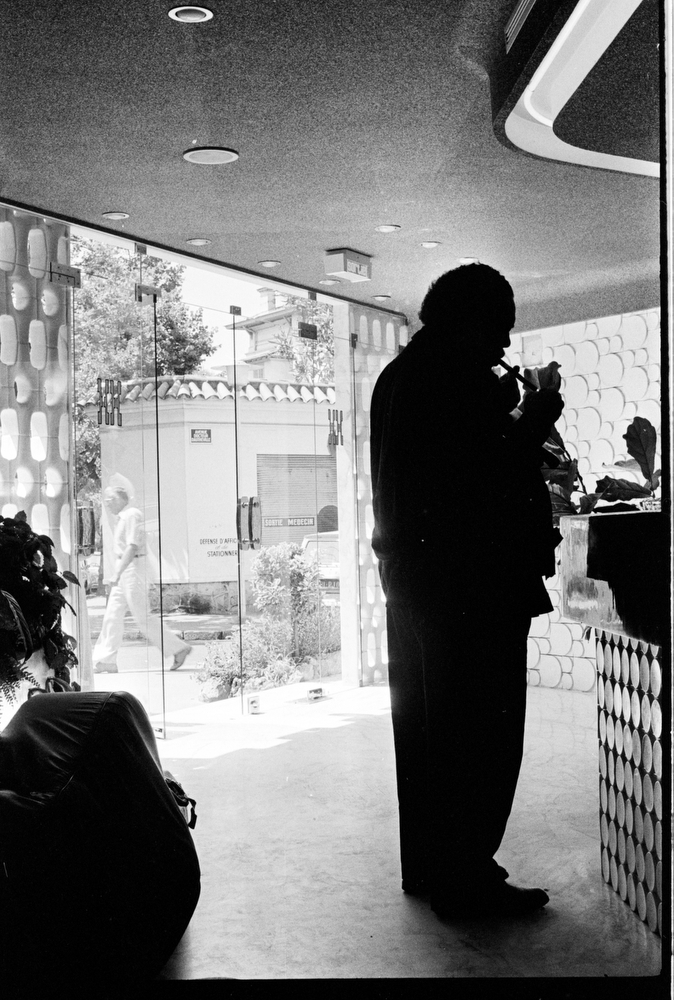

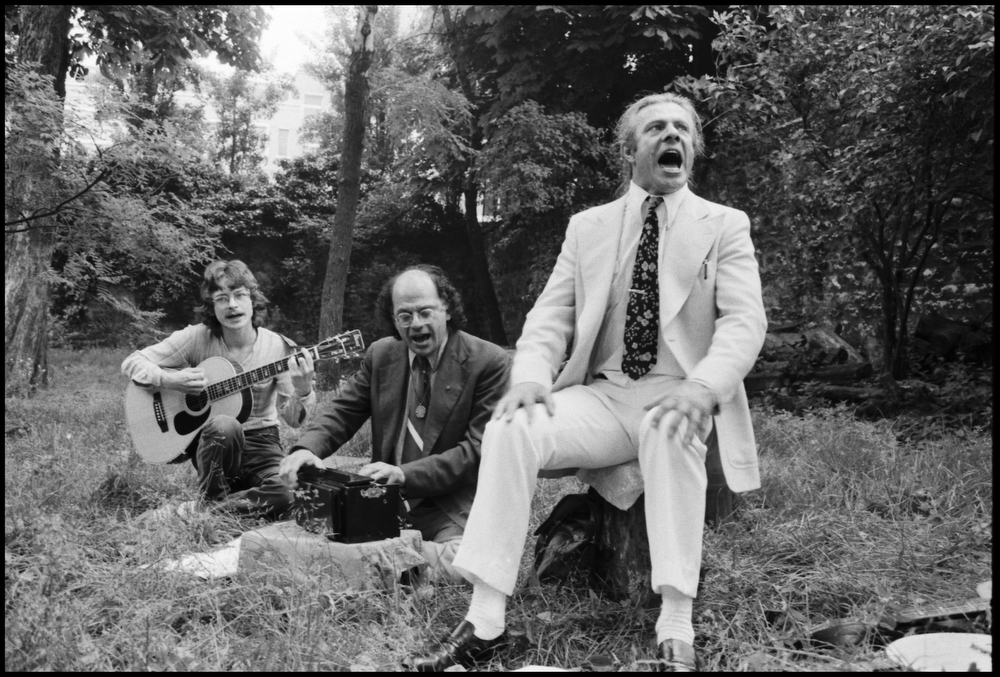

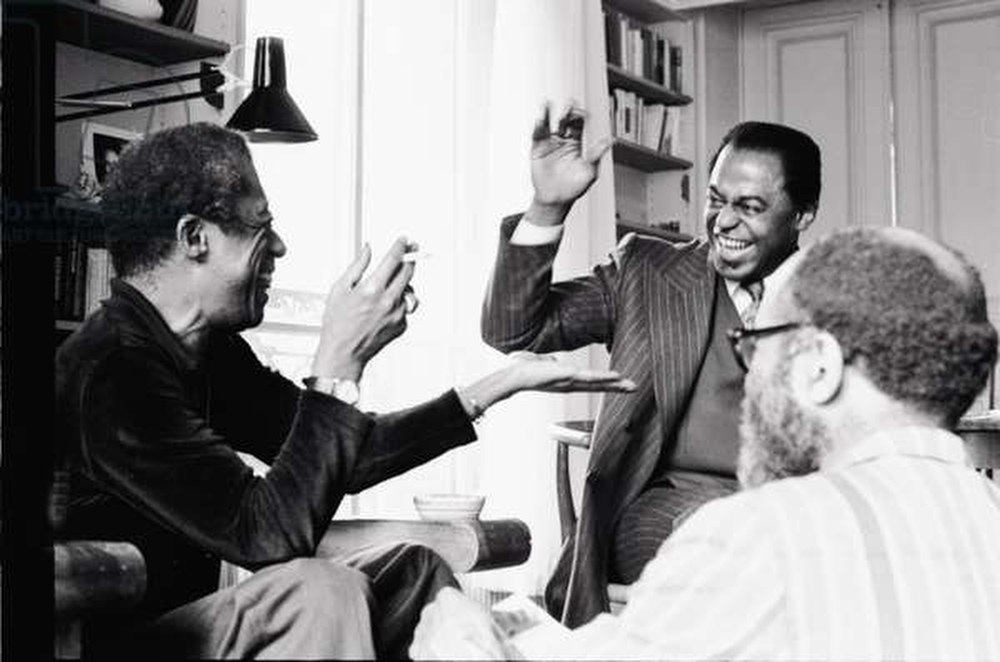

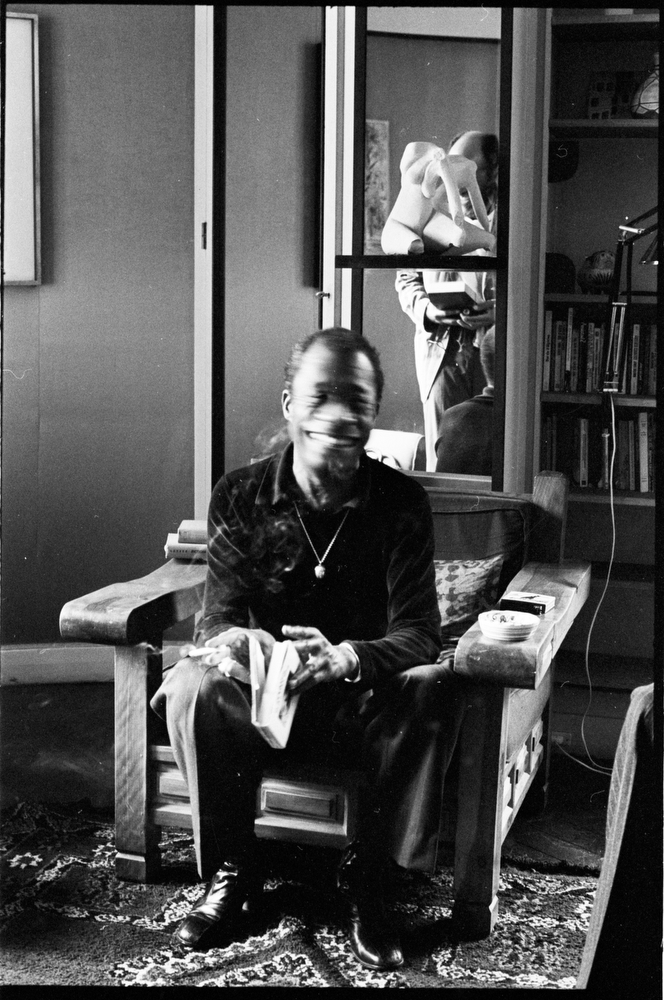

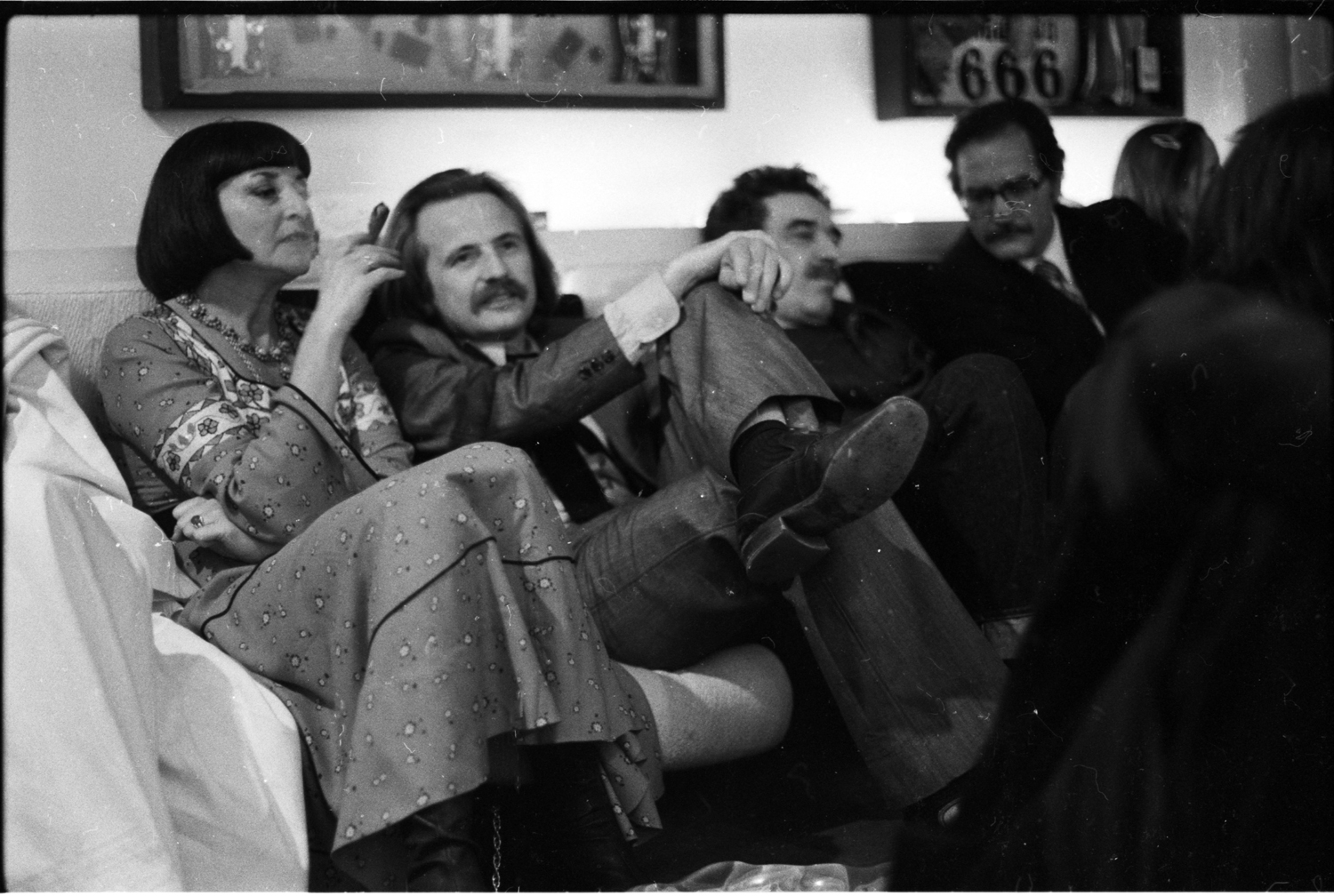

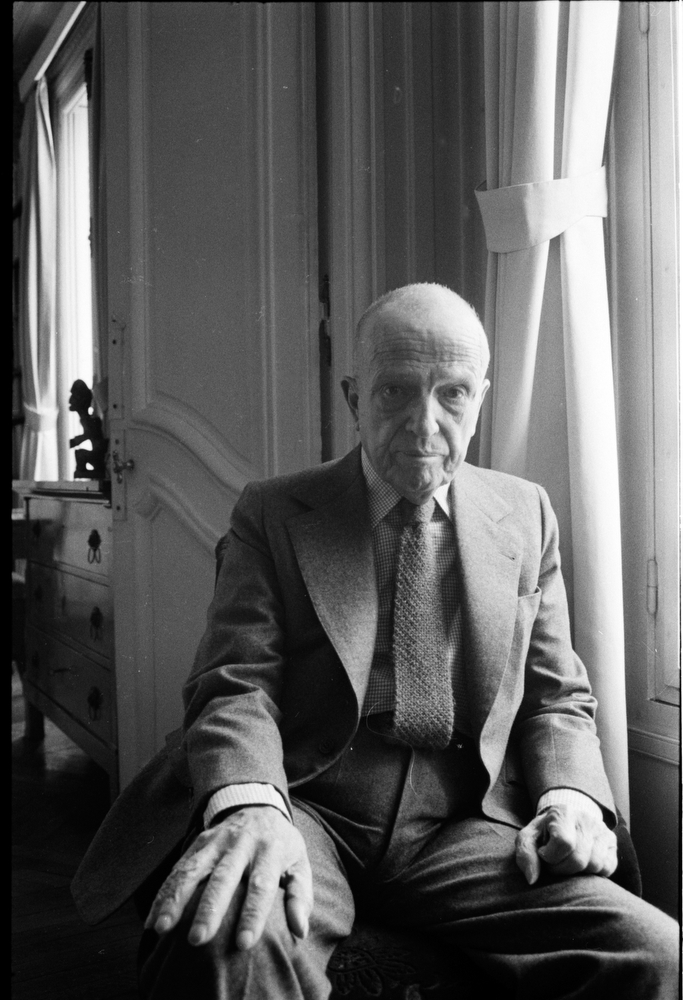

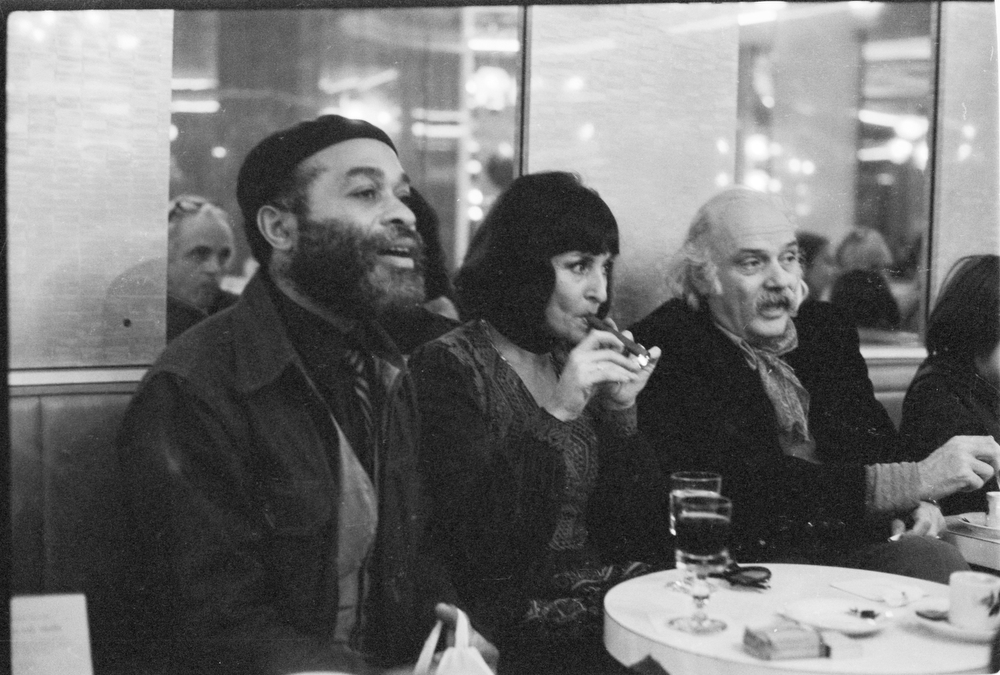

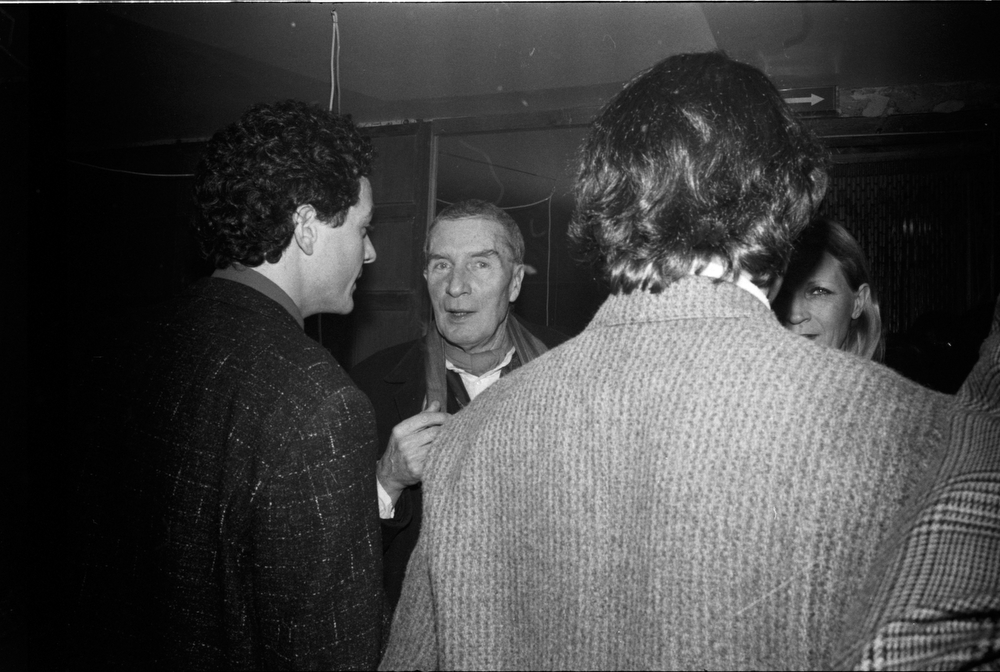

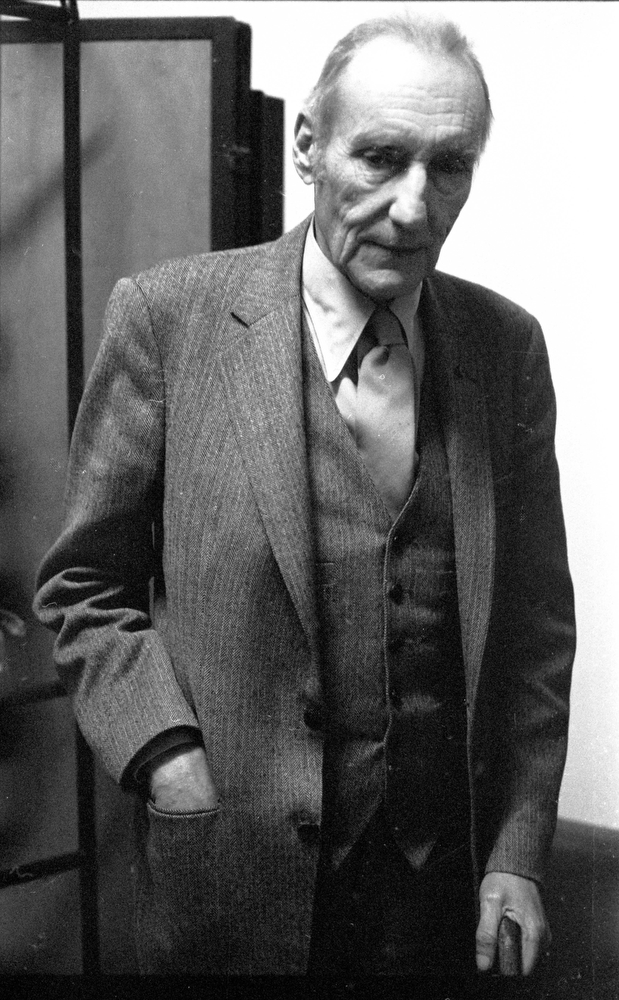

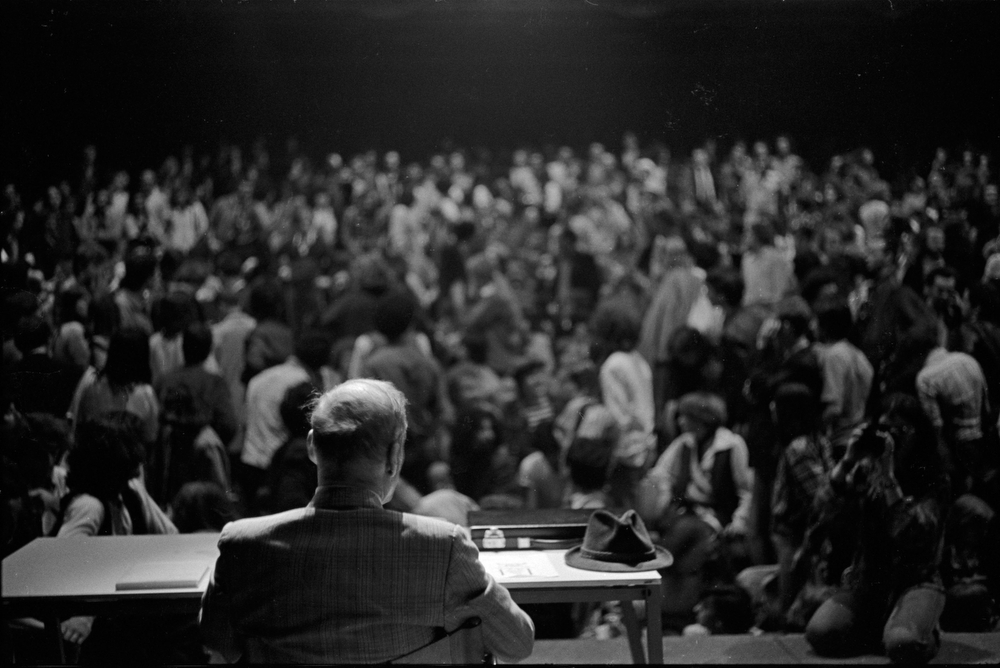

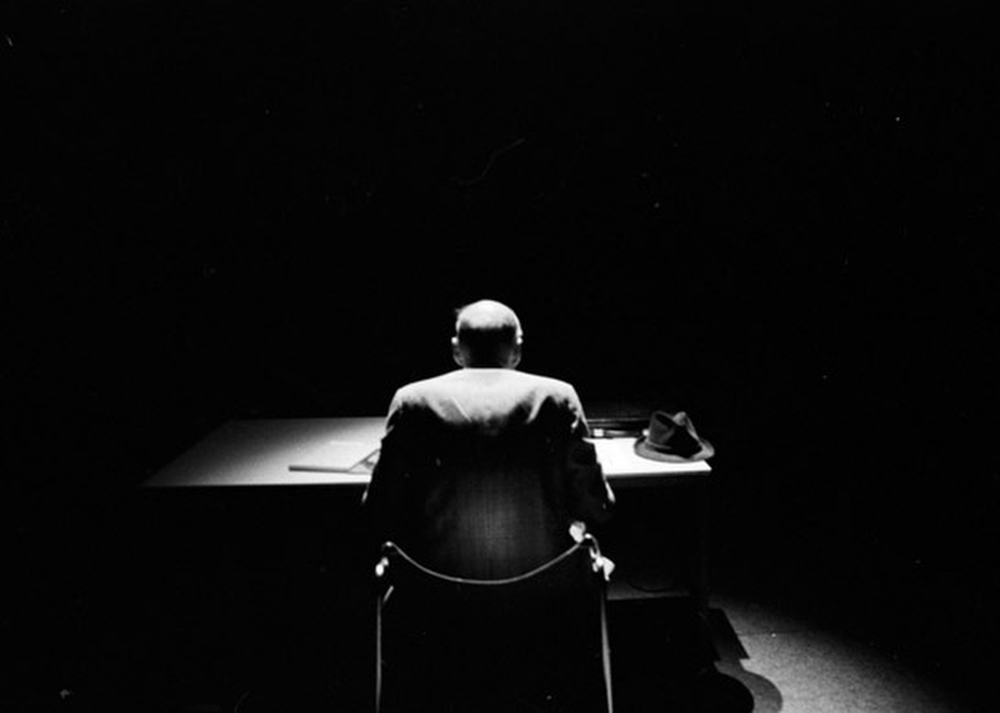

the spiritual, intellectual, and social liberation of the twentieth century. Perhaps for this twenty-four-year-old art student, now also a student of literature, the camera was the best means for her to participate in this artistic and intellectual world. Photographing Joyce Mansour, Régis Debray, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez sitting on a crowded couch (p.91); or Steven Taylor, Allen Ginsberg, and Peter Orlovsky loudly performing in the garden at the American Center in Paris (p.83); a series of photos of James Baldwin and Ted Joans that speaks of the pure joy of reunion and cooperation. Or two wonderful, yet completely different pictures of William S. Burroughs: a landscape format from 1977 with Burroughs’s back

to the camera, at a lone table under a bright spotlight in front of the yawning blackness of the space; or Burroughs six years later, this time photographed from the front, self-absorbed and almost more distant than in the previous picture (pp.75-77).

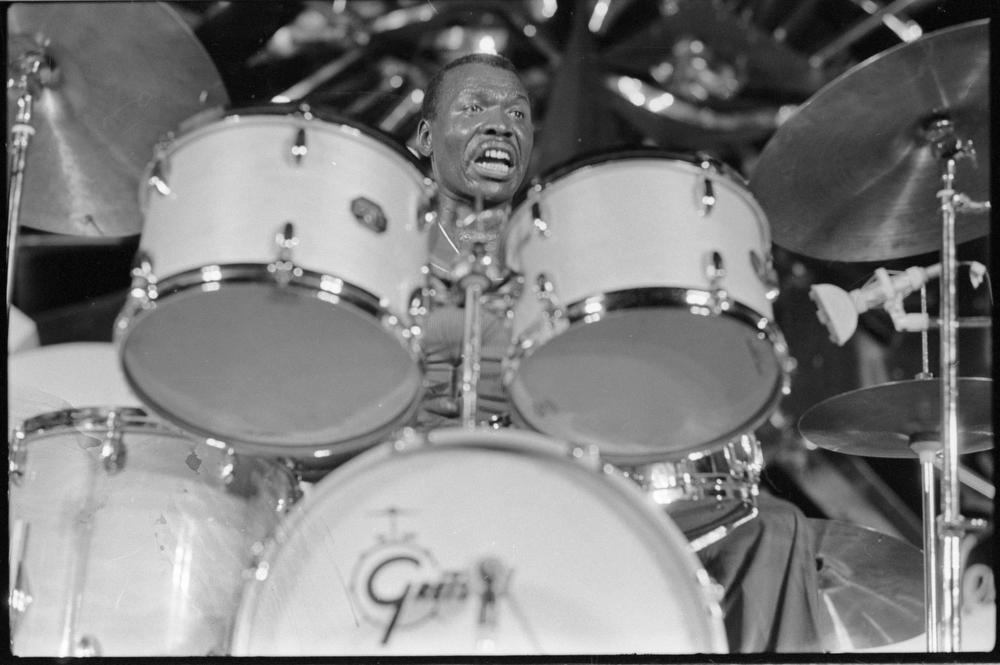

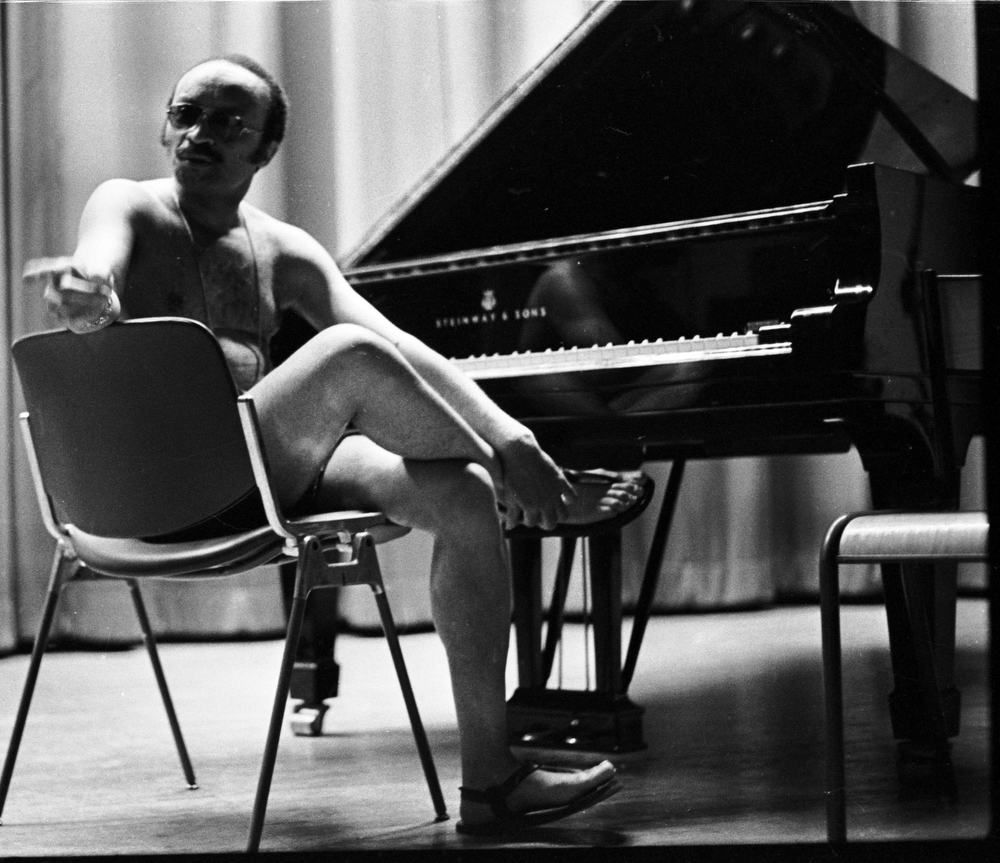

Thanks to her “Teducation”, Kalter also had access to the music world, to jazz; she photographed the festival in Juan-les-Pins, Dizzy Gillespie on stage, and Charles Mingus lighting a cigar at the bar. These photos still contain their initial magic and perhaps also the shyness of the young woman at the side of the experienced artist. She shot one of the most beautiful pictures during a visit with Ted Joans to Dorothea Tanning’s apartment, when she surprised another guest there with her camera. John Cage looks up briefly, embedded into the symmetrical composition of the image through the two spools of the tape recorder,

the two headphone cushions, and the composer’s two hands. Kalter’s picture captures an intense gaze: the

music is reserved exclusively for the composer (p.145).

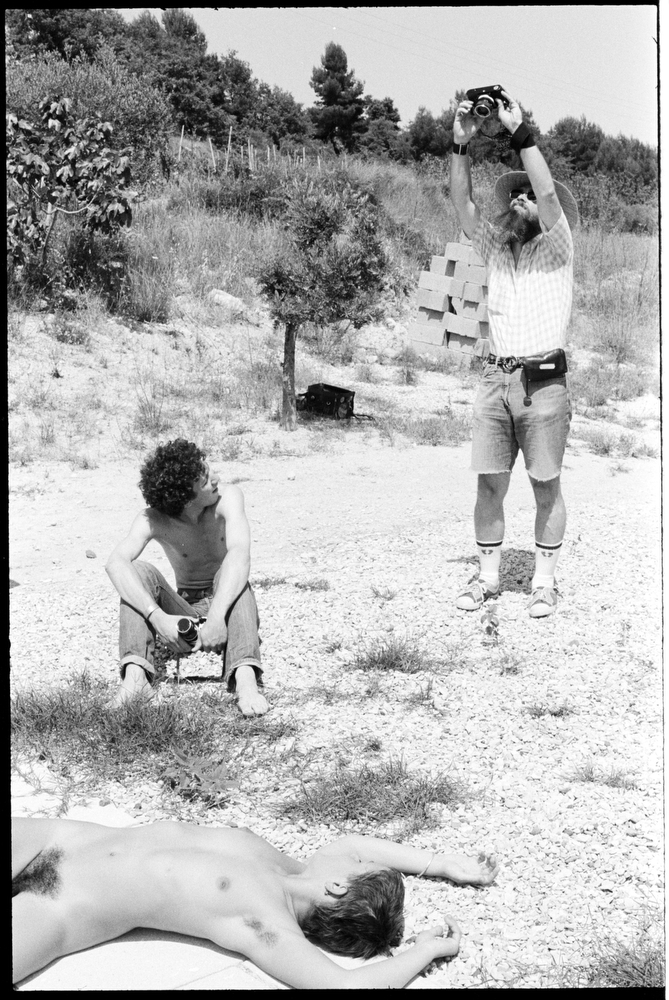

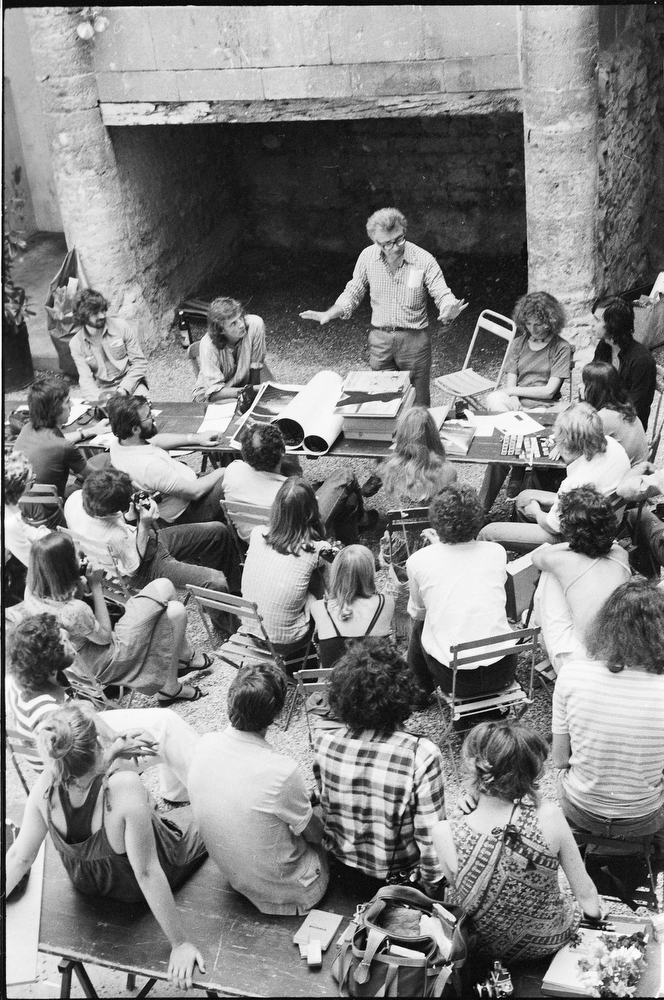

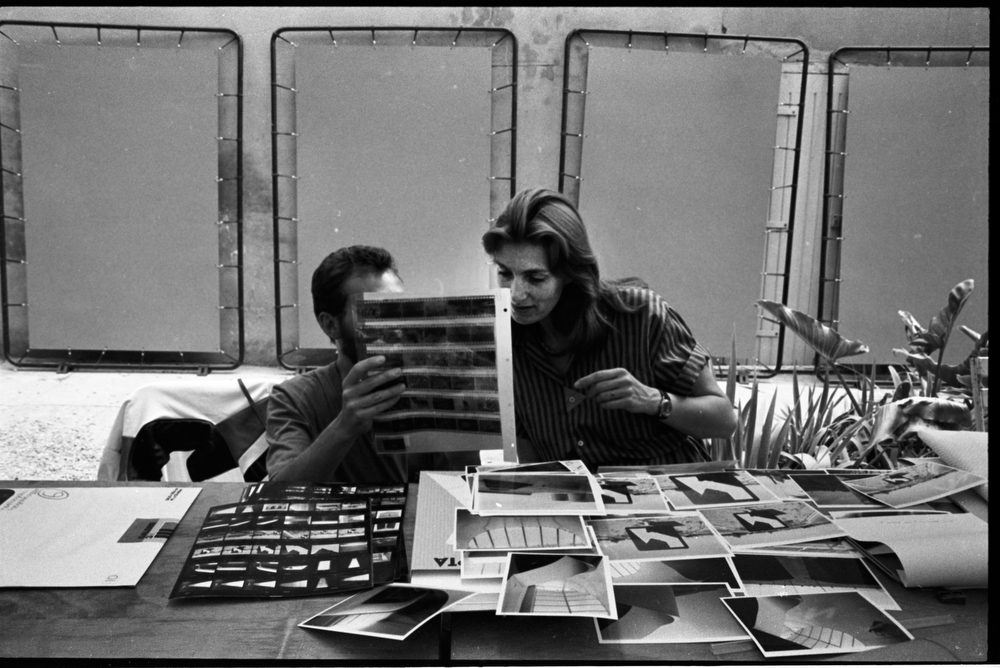

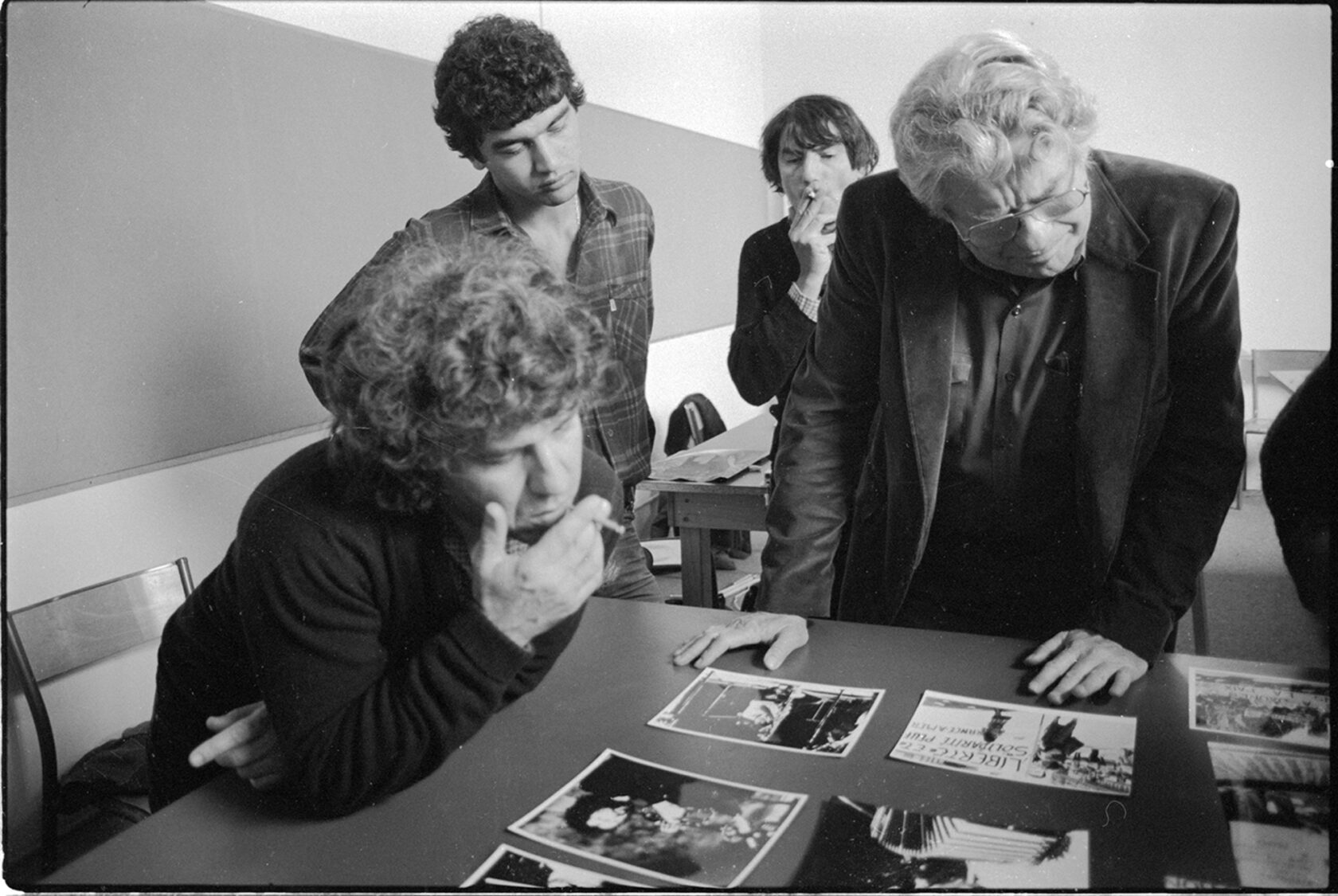

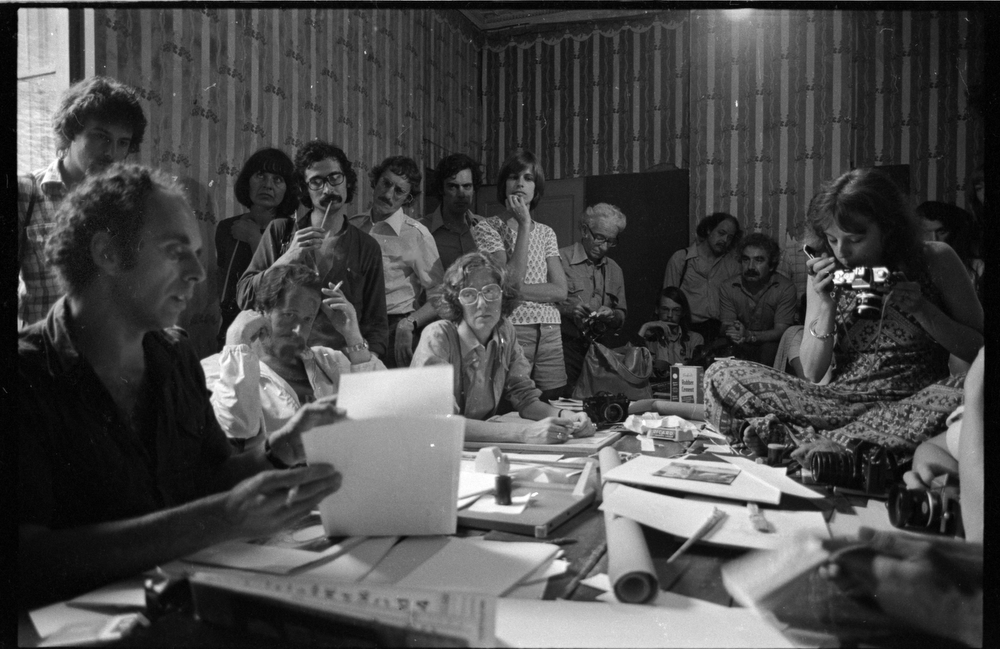

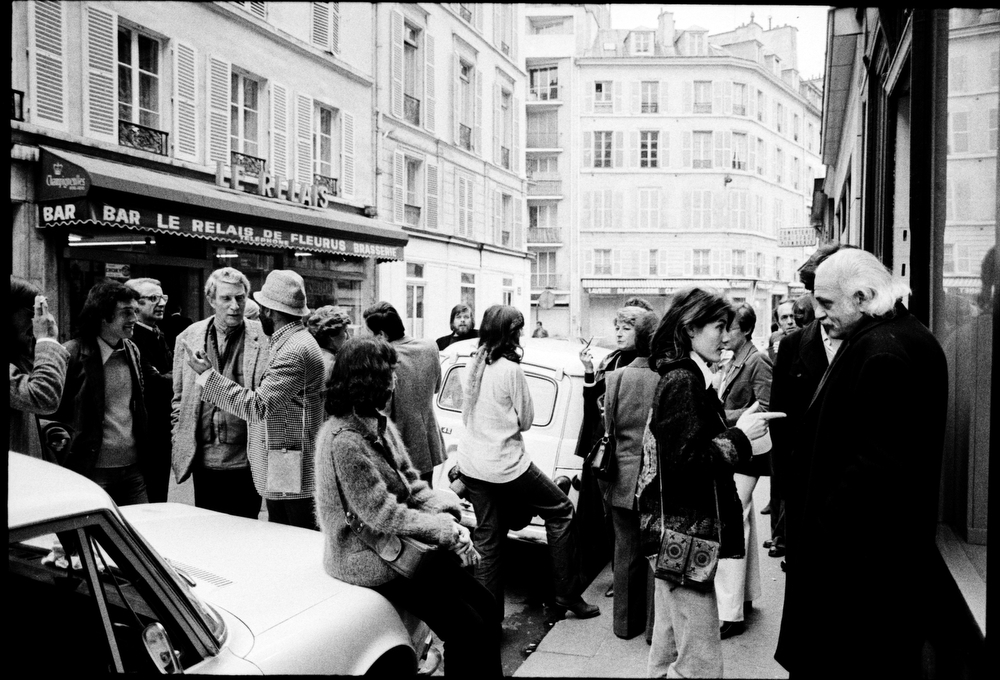

Ted Joans also arranged for her first job at one of the first galleries to dedicate itself to photography —in the mid-nineteen-seventies, when the cultural institutionalization of photography was in the making. The gallery was on the ground floor, a plate camera shop on the second floor, and the Magnum photo agency on the third floor. Since Marion Kalter spoke fluent English and German, she became a translator for the booming workshops at the still-young Les Rencontres internationales de la Photographie, a photography festival founded in Arles in 1969. It was at this moment, at the very latest, that the summer of photography began. Somewhat incredulously, with a little melancholy and almost a bit of envy, one looks at the lively activities in Kalter’s pictures of July days in 1975 and 1976 in Arles. Not only are they good photos, but they are also special documents of the now-legendary first photo workshop. The photos are almost reminiscent of Happenings, of public sit-ins, so great is the interest of the young people gathered there. For them, the small SLR cameras made by Nikon, Canon, or Olympus (Kalter holds just such a camera in front of her face in the above-mentioned mirror portraits) have become the new tools they can use to open up reality personally, poetically, or in a politically engaged manner. With cameras in their hands, around their necks, or next to them, the crowd of new photography disciples listens spellbound to Lucien Clergue, as he stands outdoors, preaching about photography. Ralph Gibson is in a small room, surrounded by at least two dozen workshop participants, giving a critique while holding a cigarette in his right hand and leafing through the contact sheets with the other: a moment of tense stillness, which allows Kalter enough time to capture the scene (p. 50). At the time Gibson was one of the key players in the transference of American photography to Europe, and picturesque Arles at midsummer was a major base camp. With his early 1970s’ series The Somnambulist, Gibson came to epitomize a kind of photography that was enthusiastically received in Arles; his mix of magical realism and graphic elegance was inhaled and imitated by an entire generation. It was a form of photography, about which you could still say to the public, “Tell me what you want to say with the camera, and I’ll tell you how to compose it so that it will be a good picture.”

For the young Marion Kalter — a translating, interpreting mouthpiece — these experiences must have been

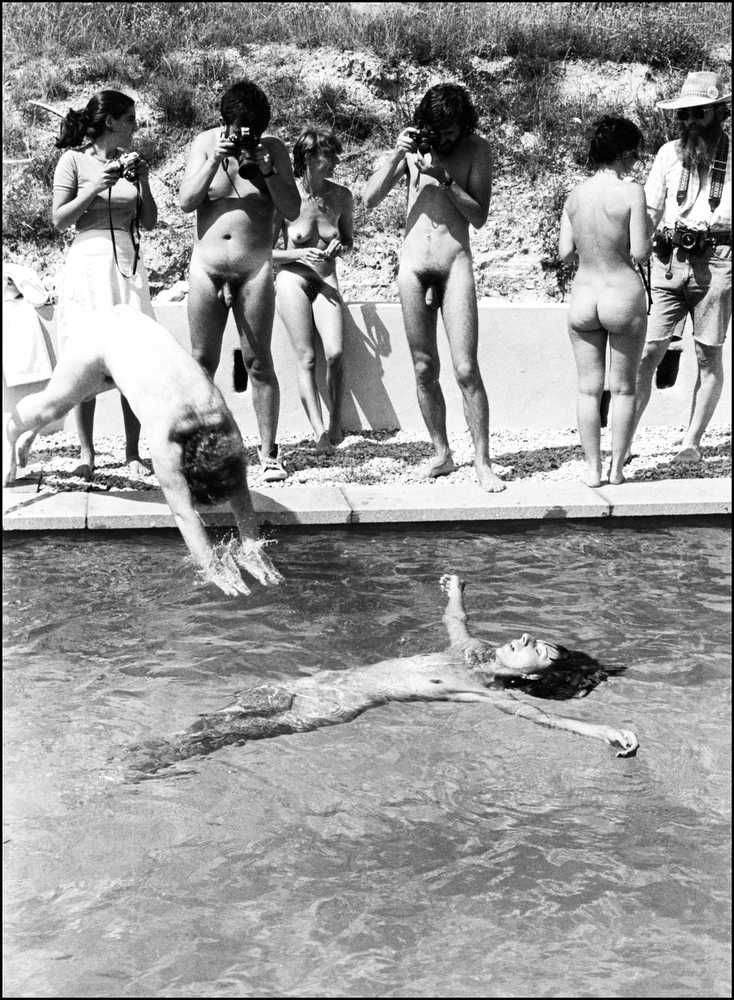

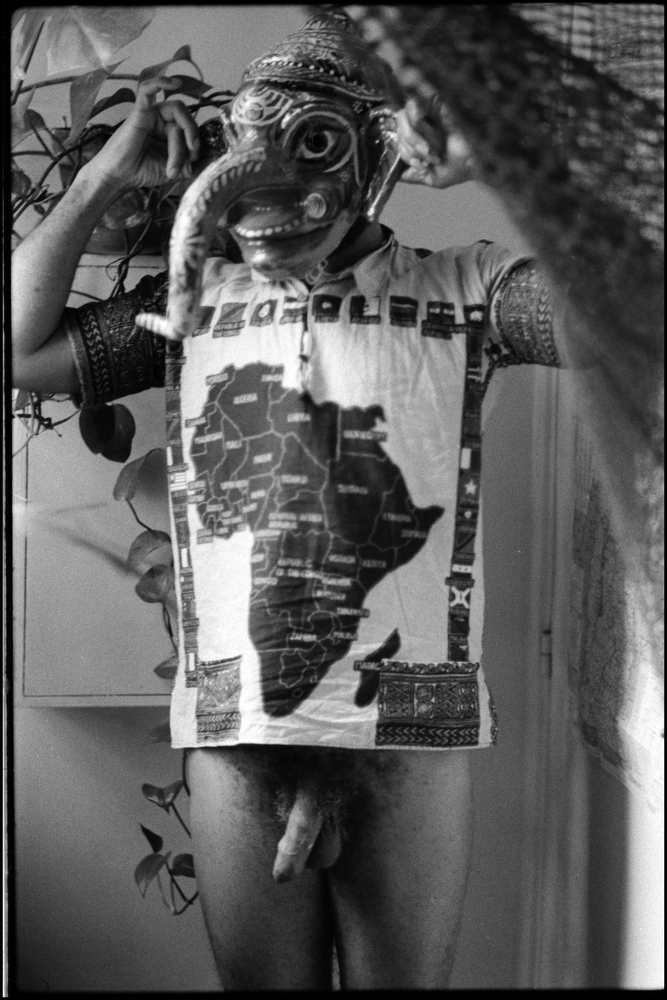

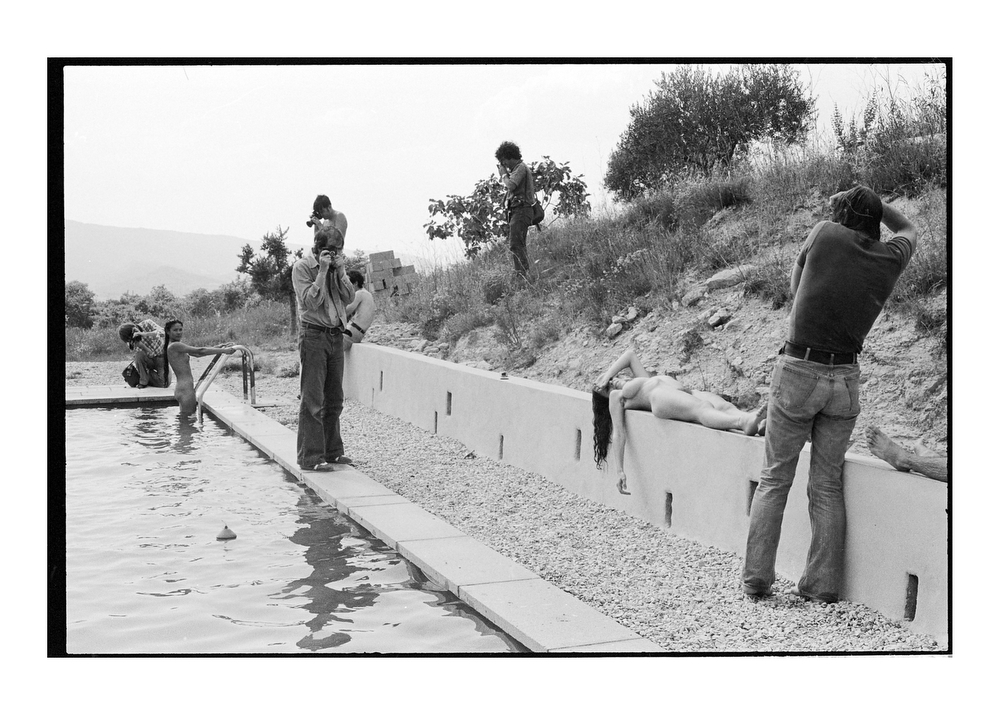

formative, as she herself said, referring to the Magnum photographer David Hurn. Besides the discussions and seminars with Garry Winogrand and Guy Le Querrec (p.51), or Verena von Gagern (a photographer whose work has fallen into some obscurity) at a table outdoors, surrounded by prints, there are also the workshops in action, at the moment the picture is taken, and one wonders about the tremendous energy released, as it is, for example, in the picture of Floris Neusüss inside a church choreographing a row of men before they become a living frieze in a life-sized, full-body photogram. The resemblance to Happenings continues in the workshops, where the ambitious amateur photographers are visiting Jean-Pierre Sudre at his home in Lacoste. Entirely in the liberating spirit of the nineteen-seventies, not only are the life-drawing workshop models naked, but so are the mostly male participants. The artistic relevance of some of these workshops is still debatable today. Kalter succeeds in capturing a wonderful, somewhat ironic picture of this: Sudre’s swimming pool also holds five photographers, including the two Magnum photographers David Hurn and Guy Le Querrec, along with Will McBride, swarming around two nude models (p. 53). At the time, the real art was probably not to allow any more of their colleagues with cameras into the picture, and yet at the same time to be somewhat reminiscent of Edward Weston in the arid southern French landscape.

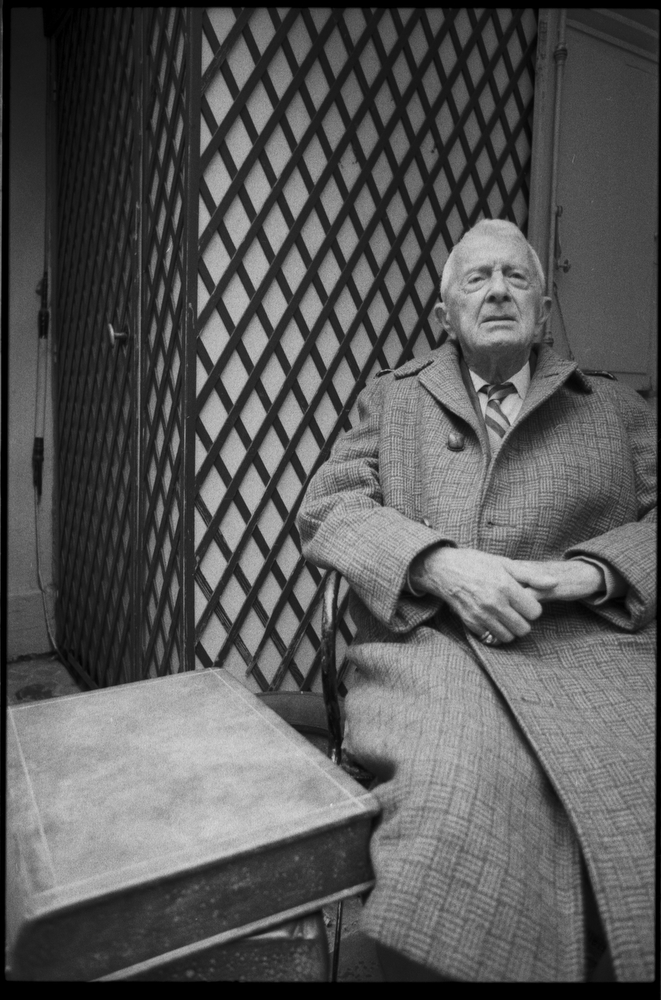

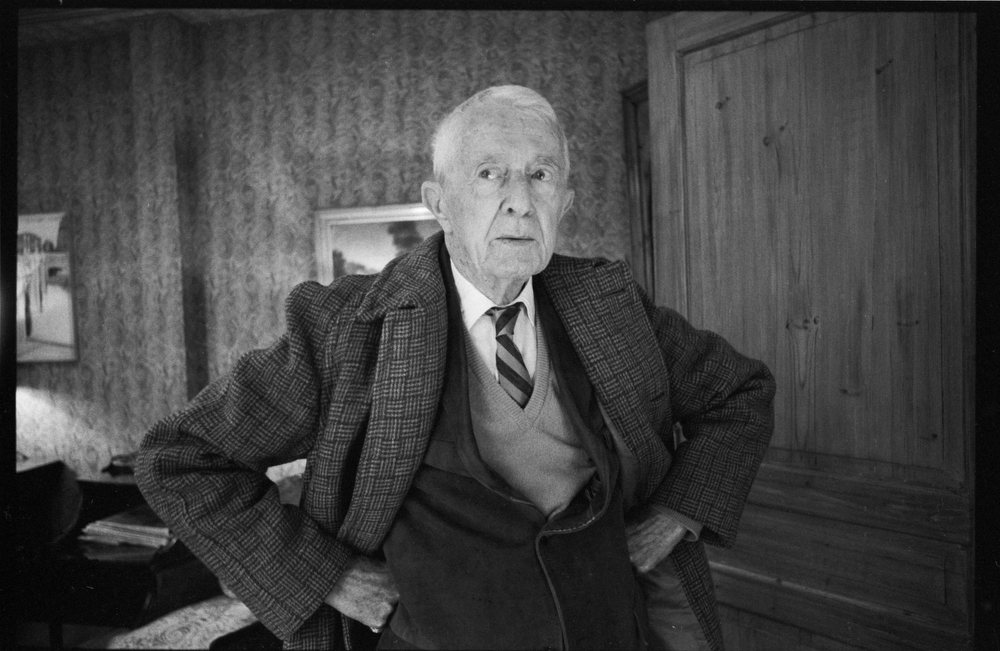

Kalter’s portraits of Parisian intellectuals and artists of the late nineteen-seventies and eighties lead us to the long summer of theory mentioned at the top of this essay. From the Parisian perspective, it was already late summer: the great anthropologist and structuralist, seventy-three-year old Claude Levi-Strauss, casts a glance over his shoulder at the somewhat awed young photographer (p.143). The two very different philosophers Emil Cioran and Emmanuel Levinas — both intellectuals who came, like so many others, from Eastern Europe to Paris — also sat for Kalter.

Cioran, in his small attic apartment in the Latin Quarter, and Emmanuel Levinas, a little collapsed in his chair, in the same slanted position as all the publications that have found a place in the armchair next to him. Both look a little skeptical or thoughtful yet acquiesce to the photographer with her French-German/Austrian-American identity.

The wonderful picture of Roland Barthes was taken in 1979, the year he finished Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Barthes takes no notice of the photographer. He is turned away from her, in profile, his gaze directed out the window or, more likely, inward (p.144). One inevitably begins looking at Barthes’s portrait with his thoughts on photography in mind, such as the passage on the various temporalities at work when viewing Alexander Gardner’s portrait of the condemned, would-be assassin

Lewis Payne: “…this will be and this has been.” 2 Do we already see in the philosopher’s averted gaze

the death wish attributed to him by some of his companions in the last months of his life—the man who, a few months after this picture was taken, would die as the result of an accident? Whether or not Barthes would have recognized himself in this photo, at the least the study of this picture certifies that we are dealing with a scholar at the window. What he would have appreciated about many of Kalter’s portraits is that they do not “overdetermine” the person portrayed, do not burden him with preconceived meaning and descriptive sense. Much is due to the fact that her images are the result of quick observations — snapshots, or, in the language of music, “impromptus,” improvisations created out of the grace of the moment, deriving their charm from the simplicity of the gesture captured or the moment chosen. The moment when Eric Rohmer briskly enters a classroom (p.125), or Robert Wilson delves into his memories during a public lecture; when Luigi Nono reaches for the camera in a recording studio (p.148), or Pierre Boulez rehearses in front of empty seats (p.147): in general, the world of music has appeared frequently in Kalter’s pictures since the 1970s, when she began regularly contributing work to a music magazine. Yet the world of men is only half of the Parisian art world, and in Kalter’s oeuvreit is an even smaller share.

The women’s liberation movement of the nineteen-seventies left a lasting mark on Kalter’s work, as evidenced by more than just the wealth of portraits she devotes to women authors, artists, and photographers.

Let us begin with the grand old ladies of modernism who found themselves exiled in Paris: Lotte Eisner, the grande dame of film studies, reads for the photographer from her book The Haunted Screen in 1983, the year of her death (p.124); there is a very early picture, from 1974, of the writer Anaïs Nin, author of the most intimate experiences, with a fathomless smile. Kalter produced a special photo in 1979 when she shot portraits of the two photographers Berenice Abbott and Gisèle Freund together in the Paris branch

of the Zabriskie Gallery, another bridgehead for American photography in France (p.126). Neither of them

would have met during the interwar period in Paris, as Berenice Abbott left Paris in the late 1920s to return to the United States. Gisèle Freund, on the other hand, left Frankfurt and Nazi Germany in 1935 to settle in Paris, where she photographed the intellectuals of her time and wrote the first social history of photography. In Kalter’s photograph the two are not talking to each other. Freund carefully examines the photography on the wall, while Abbott sits there like a sphinx, a living monument to the history of photography. In the portraits of the younger generation of authors and artists one notices that they appear to be in control in front of the camera, anxious to present the right image of themselves. Annette Messager poses for her portrait in front of a few of her own works, whose theme is the question of self-perception and the perception of others (p.137). The writer Susan Sontag, author of the essay “On Photography,” with an impressive mane of hair, looms large in the image; the previously mentioned portrait of Chantal Akerman in front of the poster for her film Jeanne Dielman, whose protagonist became an icon of the radical feminist approach; the large eyeglasses of the artist Joan Mitchell correspond wonderfully to the reverse of the frame (p.122). The Egyptian-born Joyce Mansour sits at the window, with the figure of a bird behind her, as if it were the author’s alter ego or a hieroglyph of her identity (p.132). What may be Kalter’s most beautiful portraits of women artists are scenic portraits, taken in the apartments and studios of her models. The wonderful, amiable, virtuoso filmmaker and photographer Agnès Varda is still sitting in bed, next to a 16mm projector, lecturing with her own special charm (p.120). Or Gina Pane, one of the major figures on the Body Art scene. The radicality of her performances, which also included injuring her own body, is not visible as she poses for Kalter’s camera, and yet the generosity of her outstretched arms, the doorknob firmly in her grip, show that her body must be her means of expression (p.123).

In a conversation about her photography, Kalter once spoke very openly and directly about what is going on with her pictures. She never became a perfectly geometrical artist whose photographs were always meticulously composed, like Henri Cartier-Bresson, for example.

What always counted for her was participating in the moment. If one asks Kalter about the fruits of the long

summer of photography she was able to harvest, it really has to do with that kind of witnessing. She is often not concerned with a single moment but with various and sundry temporalities stemming from the examination of her family’s history and the story of a woman who, at the age of sixteen, had to face the deaths of her mother and grandmother. Different Trains is the title of one of her most recent series (pp.171-175). Her title is taken from a Steve Reich composition commissioned in 1988 for the IRCAM in Paris, an institution that is part of the Centre Pompidou, for which Kalter often worked.

Steve Reich’s composition harks back to his many childhood trips between New York and Los Angeles

in the early early 1940s — train trips that would have looked very different to him if he had been the son of

a Jewish family in the European land of the Shoah at the time. For Marion Kalter the analogy is the escape of her great-uncle, also from a Jewish family, on the Trans- Siberian Railroad through the Soviet Union in the year 1940. Kalter herself undertook this journey on approximately the same stretch around seventy-seven years later in 2017, in a couchette coach from Moscow to Beijing.

A special portrait of her father — a German Jew and naturalized American, an attorney and joint plaintiff in the IG-Farben trial, a jurist who worked for NATO, stationed first in France and later in Heidelberg, Germany — shows us nothing of his face; rather, the photograph withholds it from us, hidden behind a Groucho Marx mask, as he sits in his office with a map of Germany behind him (p.165). Perhaps this image is also a kind of hieroglyph of a twentieth-century identity.

Photography Means Participation is the title of an important exhibition on women photographers of the

Weimar Republic; perhaps this phrase also applies to the 1970s’ generation and in a special way to Marion Kalter.

For her, whose life in Austria, Germany, France, and America taught her many languages, photography has become a kind of “intimate language” as she herself once described it, which she practiced when she could hide behind the camera and yet at the same time participate in the world of intellectuals and artists. Last, but not least, the camera — the Olympus she holds in the sequence of self-portraits taken in front of the mirror in Arles—has become a tool for exploring her own life, from the early self-portraits on the family sofa to, most recently, in her parents’ attic — and this is another series waiting to be discovered in this book.

1 _ [Translated] Published in English as Phillip Felsch, The Summer of Theory: History of a Rebellion 1960-1990, trans. Tony Crawford (Cambridge/Medford: Polity

Press 2022).1 _ Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang 1981), 96.

other

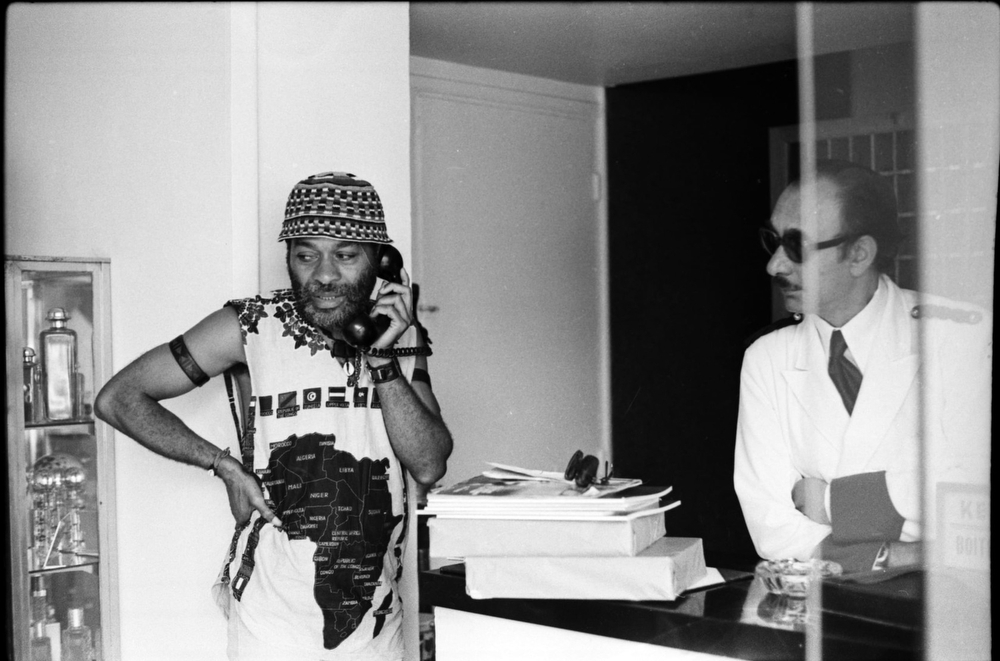

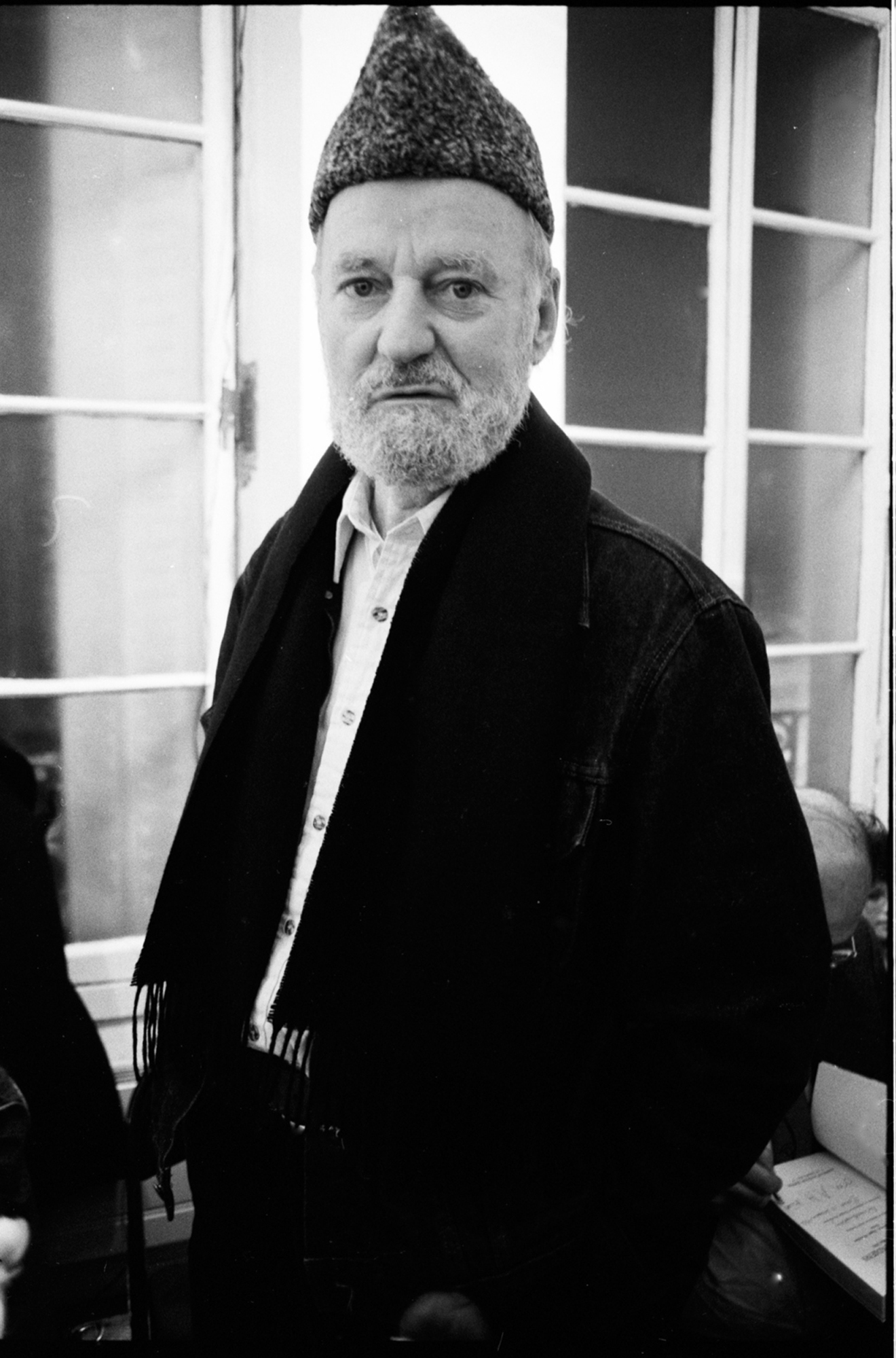

3836227 James Baldwin, Archie Shepp and Ted Joans; (add.info.: James Baldwin, Archie Shepp et Ted Joans, American author, jazz saxophonist and trumpeter. Paris, 1975); Photo © Marion Kalter; .

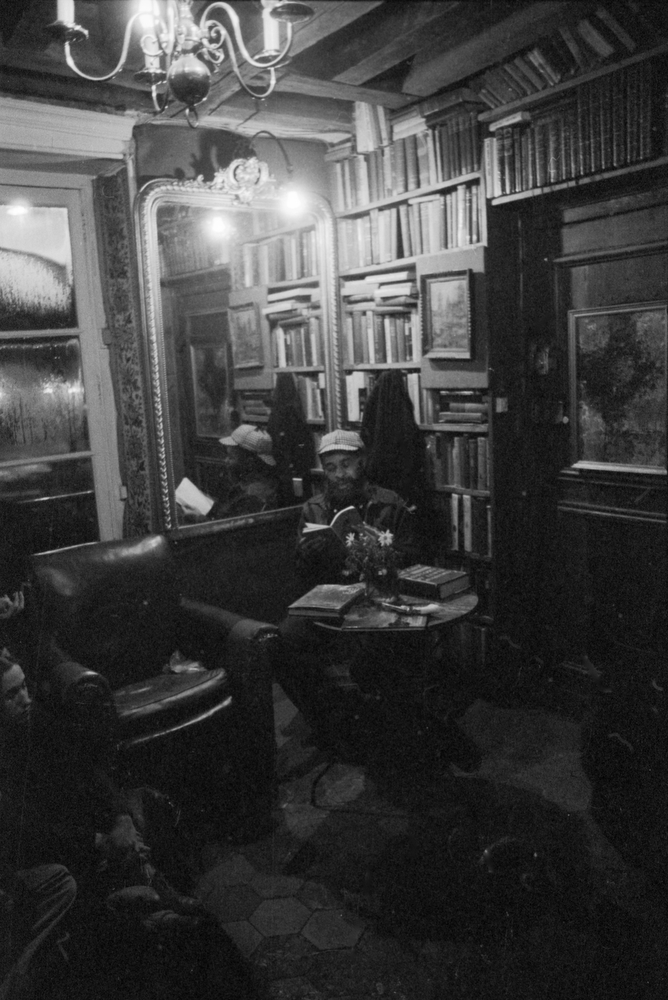

william Burroughs reading, paris 1977, centre pompidou

portrait Marion Kalter by Manfred Willmann Arles 1976