Marion Kalter

Photographs

Portraits

The frame and the void

Renaud Machart

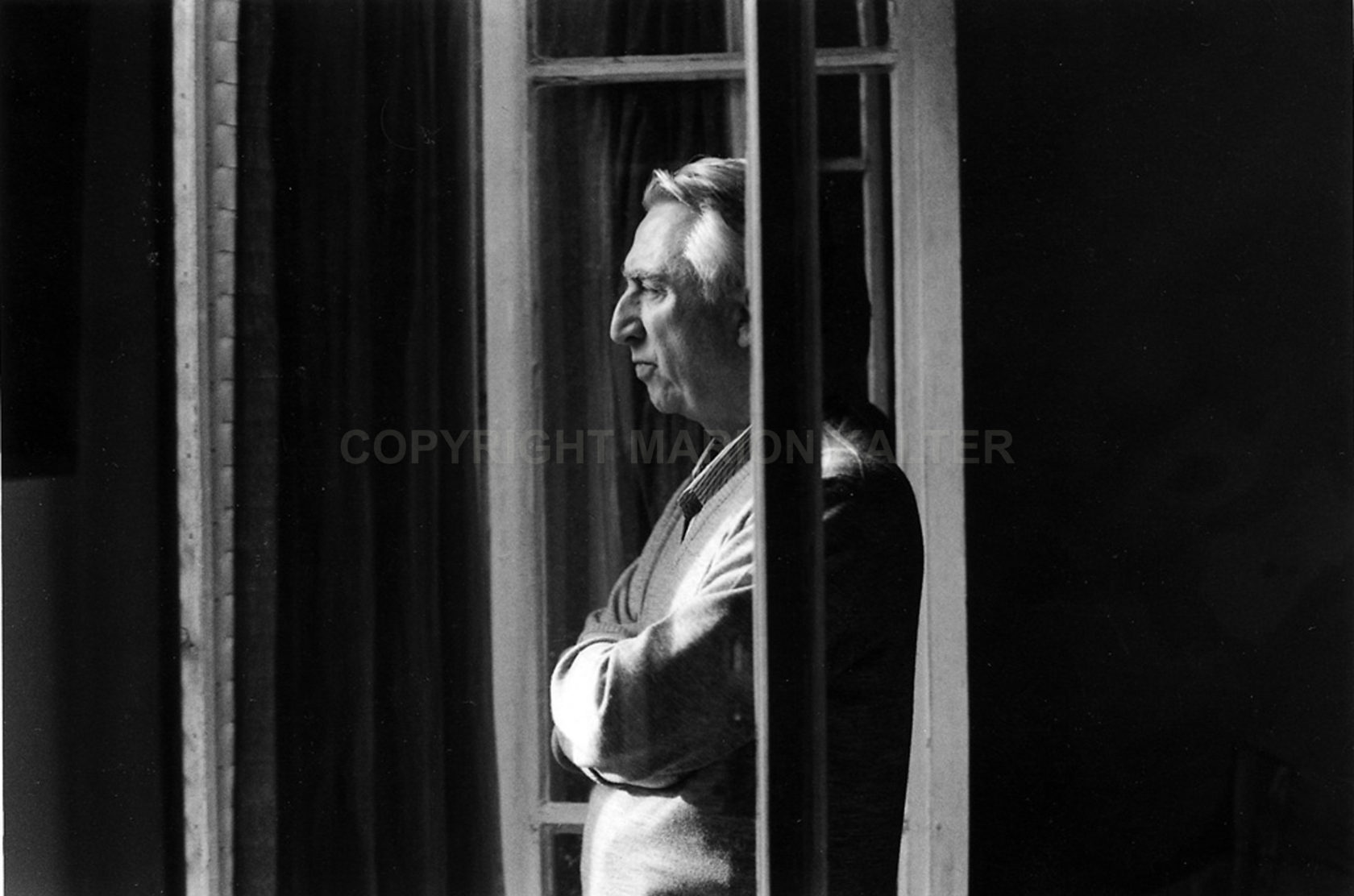

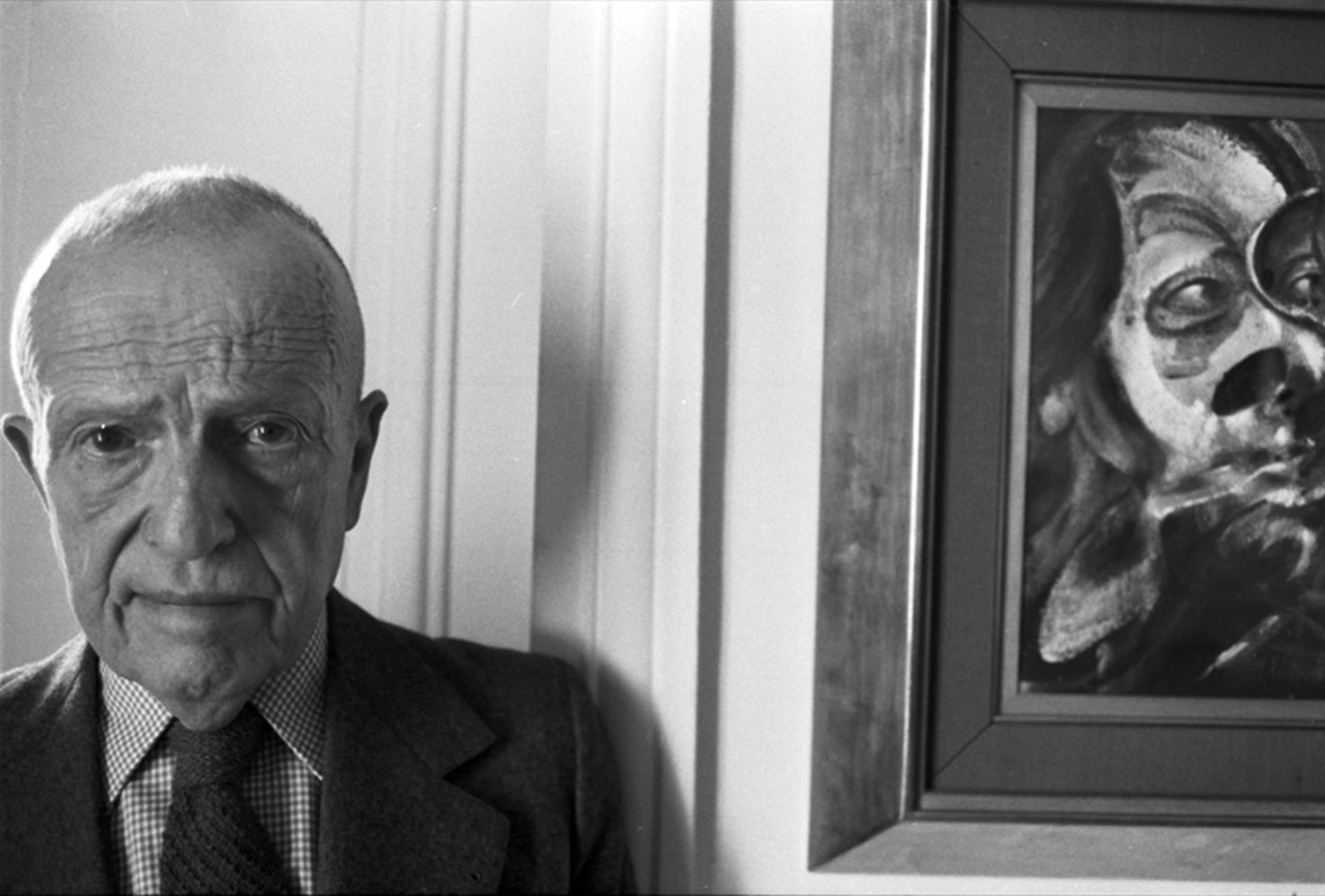

Many of the people photographed here by Marion Kalter have reached their prime – they are “hors d’âge,” as people say of the most distinguished liquors – or are almost spectral, mummified, like Martha Graham who, in the moment captured here by the lens, seems to have come out of a timeless Kabuki play. And here’s Georges Auric, the one-time enfant terrible of the roaring twenties, looking as if he’s about to present the sword that symbolises his dignity as a member of the Institut de France. Nevertheless, almost all of these individuals exude an enviable vitality which is by no means at odds with Hermann Hesse’s words, recalled by Laurence Benaïm in her fine essay, Le plus bel âge [The oldest Age] (2013): “Old age only becomes a poor thing when it tries to imitate youth.” Take a look at Leonard Bernstein – though he is far from the oldest in the room – trying, as he did with everyone (apart from the Pope, that is), to kiss his old friend Lukas Foss on the lips; look at Henri Dutilleux, at almost eighty, striding along like Lieutenant Columbo in a hurry, or the august Vladimir Jankélévitch, as handsome as Franz Liszt as an old man, with a streak of white in his hair. Some of the subjects are placed in front of an altar of some kind: the film director Agnès Varda, lying in bed with a projector beside her, leaning against a bedhead that looks like a reredos; the composer Germaine Tailleferre, sitting in front of her ornaments, formally displayed in glass cabinets framing a rather austere portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach; Lotte Eisner, for many years Chief Curator at the French Cinémathèque and venerated by Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders, her hair-do as elaborate and luxuriant as the frame of the small mirror hanging above her head, and the writer Michel Leiris, in front of one of his portraits painted by Francis Bacon, whose importance he was one of the first critics to recognize. (And there’s Francis Bacon himself, in another photograph, looking much like his tortured subjects.) There’s Nadia Boulanger, a teacher adored equally by young American composers and concert-going old ladies, seen here in her last years, almost blind, sitting beside the young pianist Emile Naoumoff, her brilliant pupil, who is beaming with pleasure, with a photograph in the background of her younger sister, Lili Boulanger, who had died sixty years previously, and to whose memory Nadia was tirelessly devoted. And there’s a pensive Witold Lutosl⁄awski, next to a mirror in which is reflected a picture hanging on the opposite wall (Marion Kalter is especially good at “framing” frames). These frames-within-the-frame, these multi-layered quotations, are perhaps not evidence of a deliberate photographic project, but recurrences which, at the moment of choosing from among a profusion of contact-sheets, convey the sense of a series, of family likenesses, of a language and a “style”. Kalter’s modern composers are portrayed in “modern” environments, lost in an abandoned room full of machines (Pierre Boulez at IRCAM) or surrounded by tape-recorders and tapes: Pierre Henry, in his “house of sounds” and of “concrete paintings,” André Boucourechliev in his bright, tidy, very “seventies” office; John Cage wearing a headset; Steve Reich, Mauricio Kagel and Luigi Nono at their mixing desks – with another witty mise en abyme moment where Nono is being photographed taking a photograph! Iannis Xenakis, a mathematical musician, is working out his sound effects on a calculator, while Wolfgang Rihm, in professorial mode, is drawing a rhythmic sequence on the blackboard. And there’s Pierre Schaeffer, sitting in front of what looks like a spherical Brâncusi sculpture but is in fact one of the legendary Elipson “Staff Ball” speakers, in use at the studios of the Groupe de recherche musicale (GRM), which he founded. There is also Karlheinz Stockhausen, his head alone emerging behind a pile of dead leaves, like a waxwork bust from the Musée Grévin placed on a tombstone, “buried in the dark earth,” as Roland Barthes wrote of a photograph of foliage by Daniel Boudinet. Many of these subjects are dead. Some of them were already not quite “present,” like Aaron Copland, once Nadia Boulanger’s favorite student, sitting at a table in front of an overturned plate. The great American composer was in the advanced stages of dementia, and only rarely in touch with the world around him, but this photo shows him at a moment when his expression was lively, alert, almost mischievous. I am especially moved by two portraits in this series. The first is of Susan Sontag, author of the famous essays collected in On photography (1973–1977), who was so devoted both to Paris, where she is buried, and to photography. She described herself as an “eternal photographic virgin,” but in fact she loved the camera and understood composition, as we see here and see so often in the photographs taken by her friend Annie Leibovitz, reflecting a state of both relaxed affection and that “density of abandonment” that her friend Barthes spoke of in connection with Robert Mapplethorpe’s Young Man with his Arm Extended (1975). And lastly there is Roland Barthes, standing at his window, lost in thought, expressionless – neither happy nor sad, neither present nor absent, drifting but not vague, the man who wrote such beautiful things about photography in Camera Lucida (1980). But one of his most astonishingly banal remarks is to be found in Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes (1977). In the margin of a photo of himself as a toddler, he wrote: “Contemporaries? I was learning to walk, Proust was still alive, and finishing La Recherche (1913–1927).” Sontag sees it differently: “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” To conclude: in that blink of an eye – the shutter is essentially a blink as it opens and closes – the photographer artist has entered this room; she, too, is in that bed, sitting beneath a framed picture, or covered by a white cloth, in a (fortuitous) echo of photographs by Duane Michals and Hervé Guibert, a phantom image hidden under the white sheet of the darkroom.

–

Le cadre et l’abyme.

Renaud Machart

Beaucoup d’entre les personnages photographiés ici par Marion Kalter sont parvenus à leur maturité – ils sont « hors d’âge », comme on le dit avec vénération des grands spiritueux – ou presque fantômatiques, momifiés, comme Martha Graham qui, à cet instant capté par l’objectif, semble sortie d’un immémorial spectacle de Kabuki, ou Georges Auric, comme près de passer l’arme à gauche, même si l’ancien enfant terrible des Années folles présente de face son épée, emblème de sa gloire d’Académicien.

Pourtant, presque tous exsudent une enviable vitalité qui ne contredit cependant pas la phrase de Hermann Hesse que rappelle Laurence Benaïm dans son joli essai, Le plus bel âge (2013) : « La vieillesse ne devient médiocre que lorsqu’elle prend des airs de jeunesse. » Regardez Leonard Bernstein – même s’il est loin d’être le plus âgé de la galerie – qui essaie, comme il le faisait toujours avec tout le monde – le pape excepté – d’embrasser son vieil ami Lukas Foss sur la bouche ; regardez Henri Dutilleux, pourtant presque octogénaire, marchant dans la rue en Inspecteur Columbo pressé ou l’auguste Vladimir Jankélévitch, beau comme le vieux Franz Liszt, et sa mèche blanche de jeune premier.

Certains se placent devant des sortes d’autels : la cinéaste Agnès Varda, couchée avec un projecteur installé à son chevet, adossée à une tête de lit aux apparences de retable ; la compositrice Germaine Tailleferre, devant des babioles sous verre, disposées au dessus du piano dans un agencement en orbite autour du portrait de Bach le Père sévère; Lotte Eisner, longtemps conservatrice en chef de la Cinémathèque française, vénérée par Werner Herzog et Wim Wenders, la mise en plis aussi ouvragée et moutonnante que l’entour du petit miroir qui au mur la surplombe ; l’écrivain Michel Leiris devant l’un de ses portraits exécutés par Francis Bacon, dont il fut l’un des premiers critiques d’art à saisir l’importance (et Francis Bacon, sur une autre photographie, qui ressemble tant à ses portraits torturés) ; Nadia Boulanger, pédagogue universelle adulée par les jeunes Américains et les vieilles filles mélomanes, en ses dernières années, presque aveugle, assise près du jeune pianiste Emile Naoumoff, son protégé surdoué et hilare, avec, au second plan un portrait de sa jeune sœur, Lili Boulanger, morte soixante ans plus tôt, à laquelle Nadia consacra un temple dont elle fut l’infatigable vestale ; Witold Lutoslawski, pensif, à côté d’un miroir qui réfléchit un tableau accroché en vis-à-vis (Marion Kalter cadre formidablement les encadrements)…

(Ces cadres dans le cadre, ces citations en incrustation ne sont peut-être pas les signes d’un projet photographique résolu, mais les récurrences qui, au moment qu’il faut choisir dans la vaste moisson des planches contact, créent des séries, des points de familiarité, des éléments de vocabulaire et de style.)

Les compositeurs « modernes » sont dans des environnements « modernes » : ils sont perdus dans une salle des machines désertée (Pierre Boulez à l’Ircam), entourés de magnétophones et de bandes magnétiques : Pierre Henry, dans sa « maison de sons » et de « peintures concrètes », André Boucourechliev dans son bureau clair et net, très « années soixante-dix » ; John Cage les oreilles couvertes d’un casque ; Steve Reich, Mauricio Kagel ou Luigi Nono devant leurs consoles de mixage (avec une mise en abyme supplémentaire piquante : le compositeur italien est photographié photographiant !) ; Iannis Xenakis, musicien mathématique, chiffrant ses effets sonores à la calculette électronique ; Wolfgang Rihm, en Herr Professor, traçant à la craie une séquence rythmique au tableau noir ; Pierre Schaeffer assis devant ce qu’on pourrait prendre pour une sculpture sphérique de Brancusi mais qui est l’un de ces mythiques hauts-parleurs en staff de la maison Elipson dont étaient équipés les studios du Groupe de recherche musicale (GRM) qu’il fonda…

Il y a aussi Karlheinz Stockhausen, dont seule la tête émerge derrière un amas de feuilles mortes, comme un buste de cire façon Musée Grévin posé sur pierre tombale, « enfoncé dans l’obscur de la terre », comme écrit Roland Barthes d’une photo de feuillage de Daniel Boudinet…

Beaucoup d’entre ces « modèles » sont morts. Certains n’étaient déjà plus tout à fait là, comme Aaron Copland (l’ancien élève préféré de Nadia Boulanger), attablé devant une assiette retournée. Atteint alors gravement de la maladie d’Alzheimer, le grand compositeur américain n’était plus que rarement en phase avec le monde du réel. Ce cliché le montre pourtant dans un instant où l’œil est vif et connecté, presque taquin.

Dans cette série, deux figures portraiturées me touchent particulièrement : Susan Sontag, qui aimait tant Paris (elle y est enterrée) et la photographie, auteure d’essais de haut vol recueillis dans On photography (1973-1977). Celle qui disait être une « éternelle vierge photographique » était en fait une amie de l’objectif et savait composer – ainsi qu’elle en témoigne ici et en témoignera si souvent devant l’appareil de son amie Annie Leibowitz – une attitude faite d’affectation décontractée et de « densité d’abandon », comme l’écrit son ami Barthes du Jeune homme au bras étendu, de Robert Mapplethorpe.

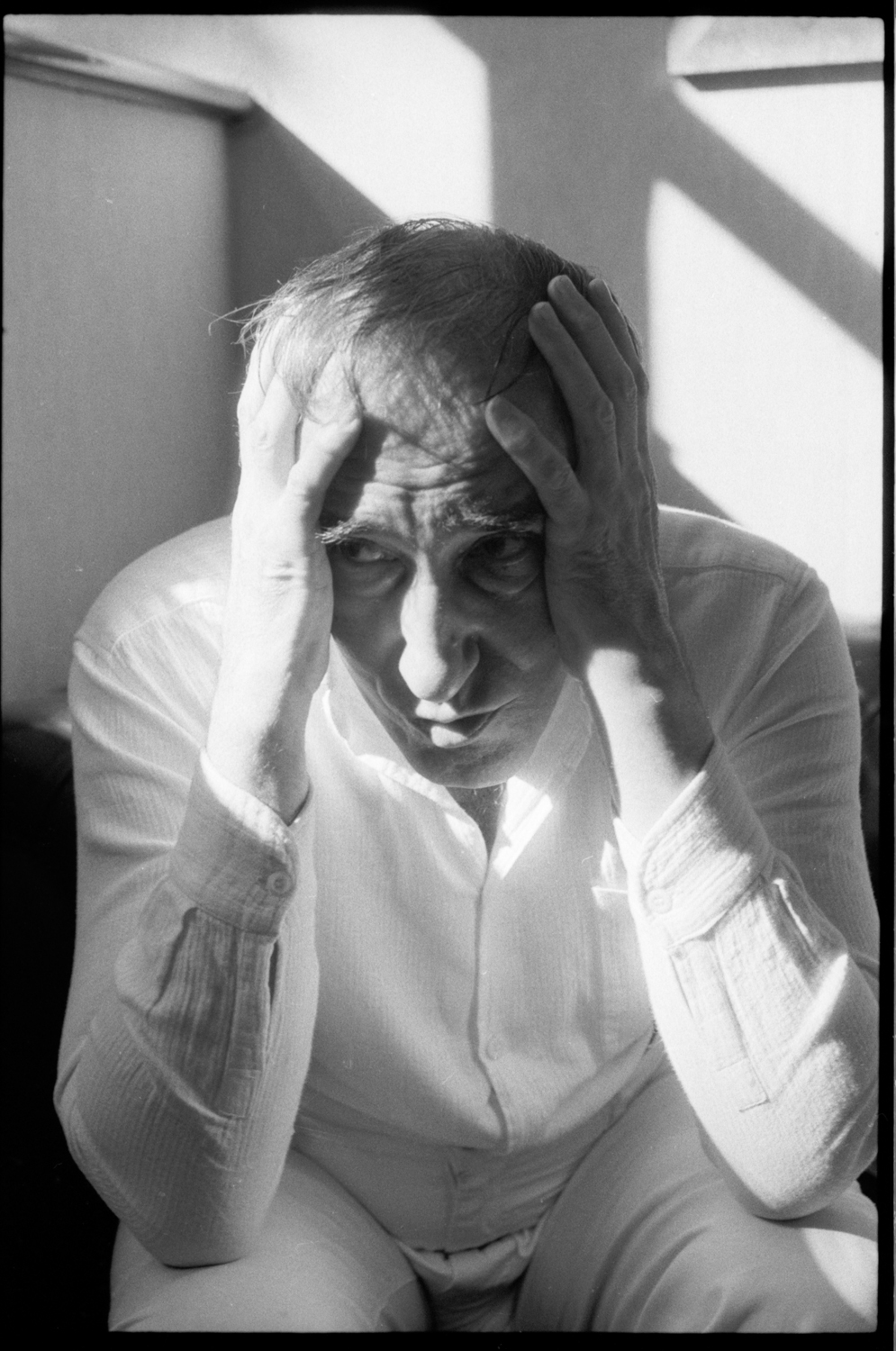

Et Roland Barthes, enfin, devant sa fenêtre, pensif, atone – ni triste ni gai, ni présent ni absent, flottant mais pas flou – qui écrivit, dans La Chambre claire, de si belles pages sur la photographie. Mais l’une de ses observations les plus banalement stupéfiantes se trouve dans Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes. En marge d’un cliché de lui encore bambin, l’écrivain inscrit : « Contemporains ? Je commençais à marcher, Proust vivait encore, et terminait La Recherche. » Sontag le dit autrement : « Prendre une photo, c’est s’associer à la condition mortelle, vulnérable, instable d’un autre être (ou d’une autre chose). C’est précisément en découpant cet instant et en le fixant que toutes les photographies témoignent de l’œuvre de dissolution incessante du temps. »

Et, pour finir, ce clin-d’œil (l’obturateur qui s’ouvre et se ferme est par essence un clin d’œil) : l’artiste photographe s’est glissée dans cette galerie, elle aussi au lit, sous un tableau encadré, et couverte d’un linge blanc, en résonance – fortuite – avec les clichés de Duane Michals et Hervé Guibert – image fantôme tapie sous le drap clair de la chambre noire.

Renaud Machart

Novembre 2013

Roland Barthes chez lui à Paris en 1979 Roland Barthes in his home in Paris, 1979

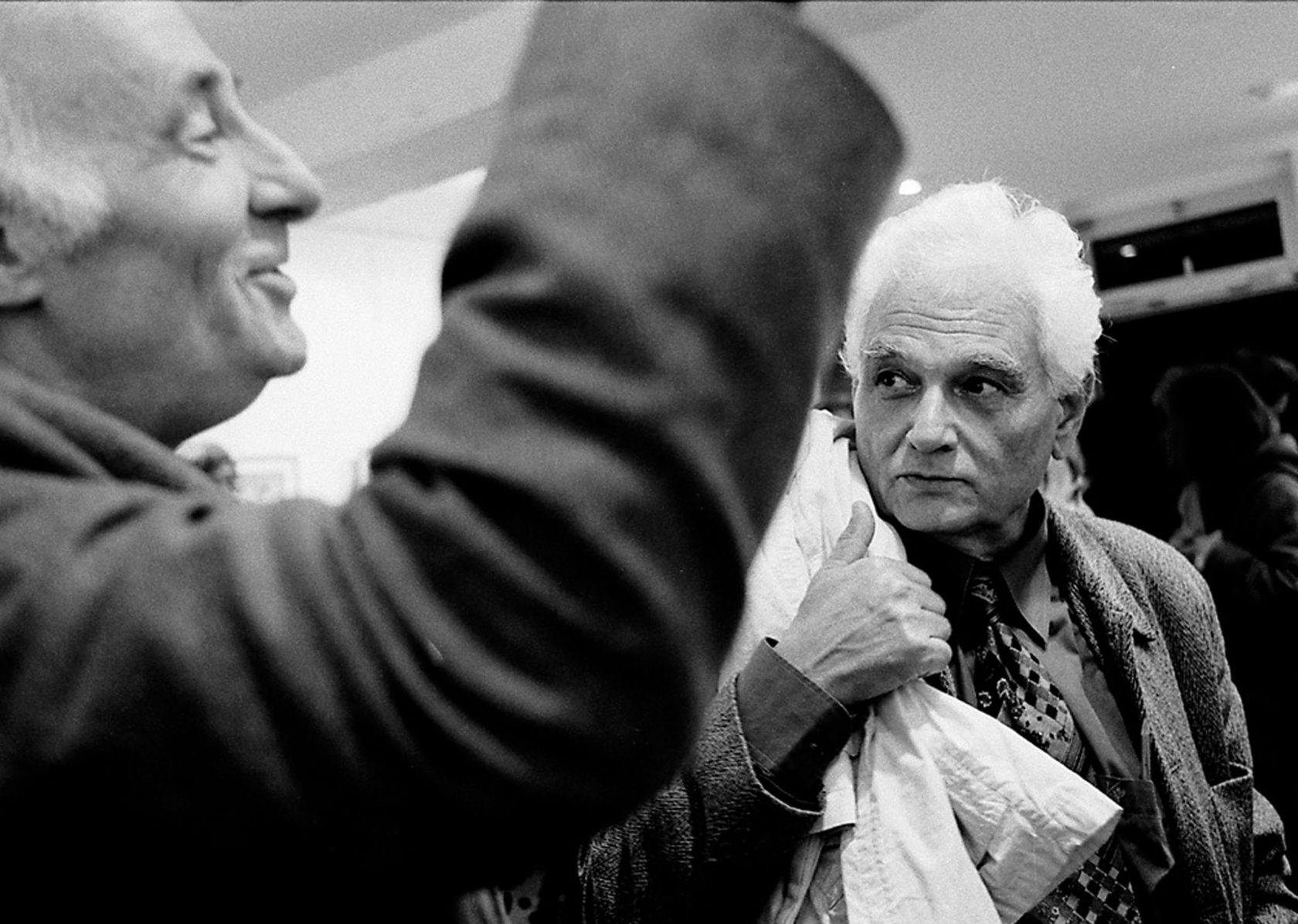

Jacques Roubaud and Jacques Derrida / Paris 1996

Yves Saint-Laurent, Paris 2001

Yves Saint Laurent, Paris 2001

Henri Cartier-Bresson photographs Jean Paul Riopelle , Tanlay 1989 / Henri Cartier-Bresson photographie Jean Paul Riopelle, Tanlay 1989

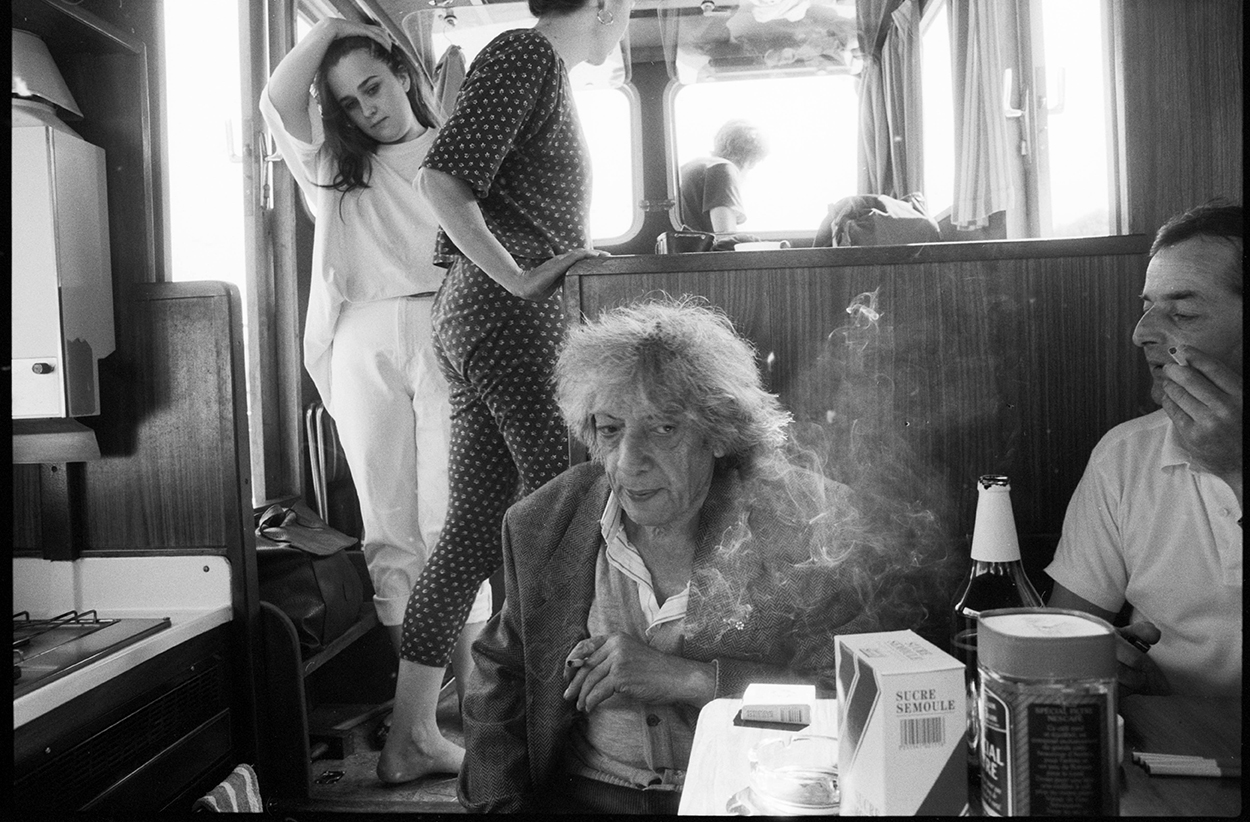

Michel Leiris, Paris 1979

Claude Levi-Strauss, Paris 2004

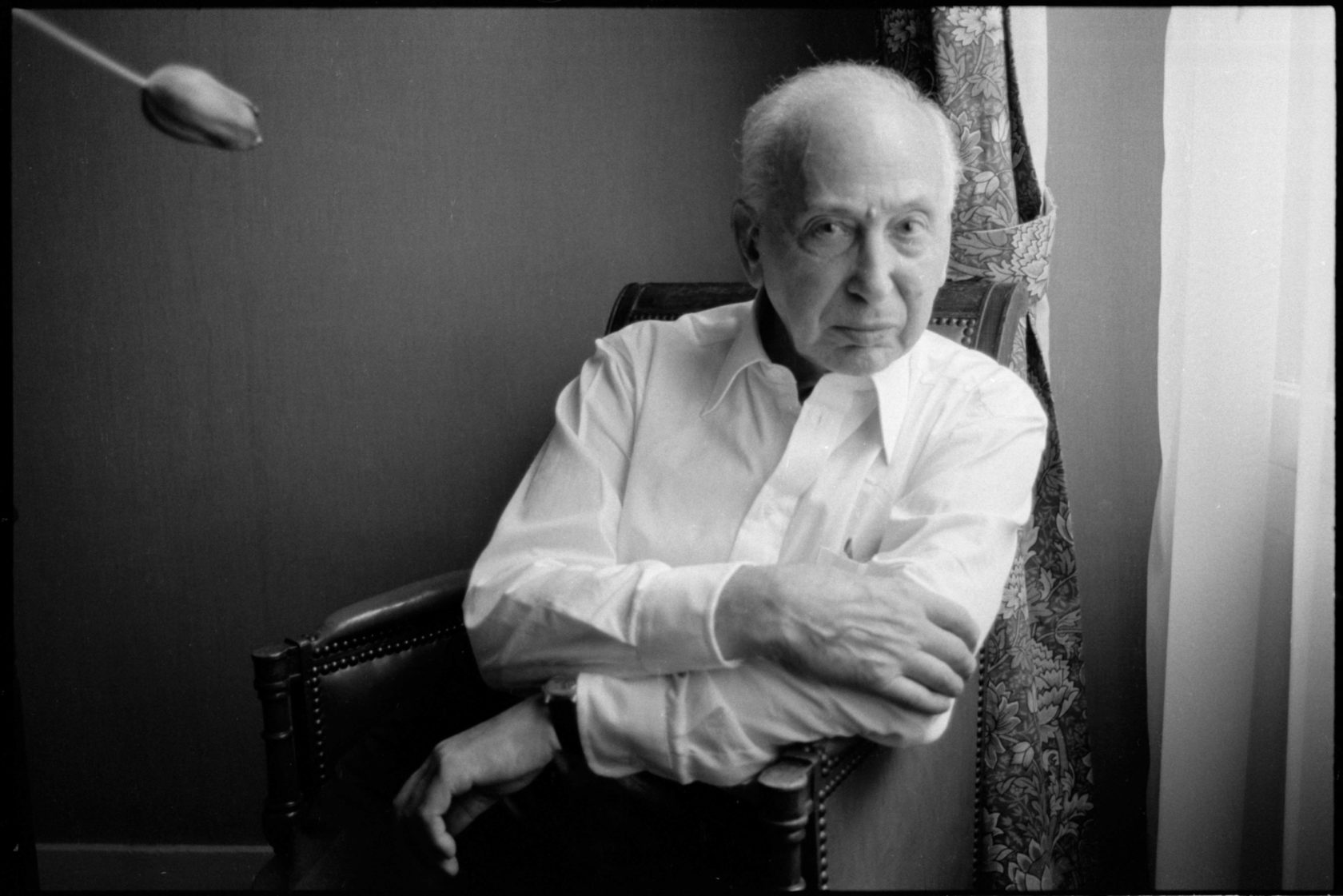

Emmanuel Levinas, Paris 1985

Andy Warhol and Alain Pacadis, Galerie Samia Saouma, Paris 1977 / Andy Warhol et Alain Pacadis à la galerie Samia Saouma à paris en 1977 andy warhol and alain pacadis at the galerie samia saouma in paris in 1977

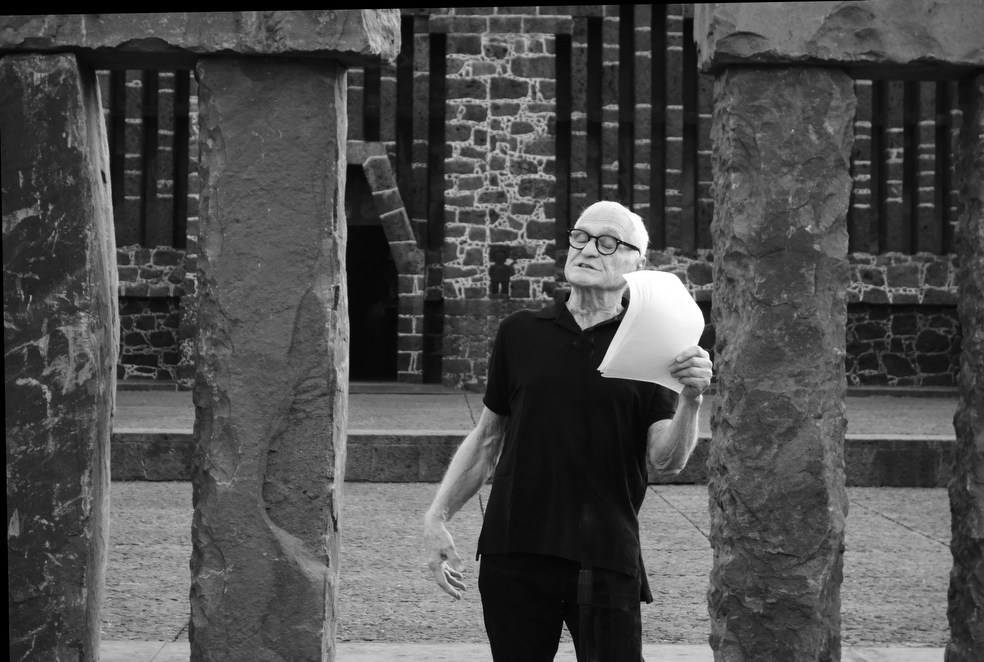

John Giorno in Mexico 2014 / John Giorno au Mexique en 2014

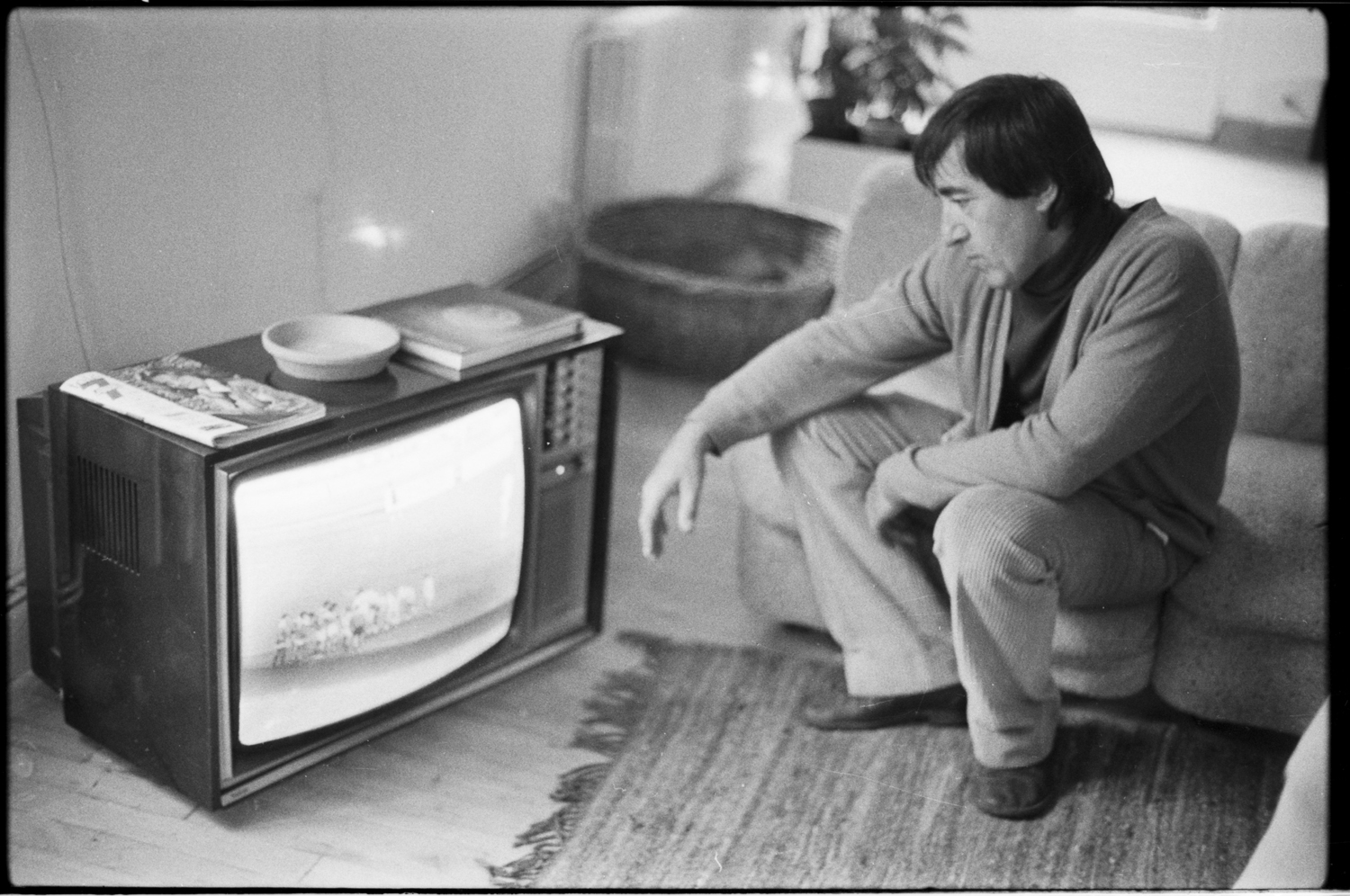

Pol Bury regarde la télévision chez lui à Paris en 1975 / Pol Bury at home watches television in Paris 1975 /

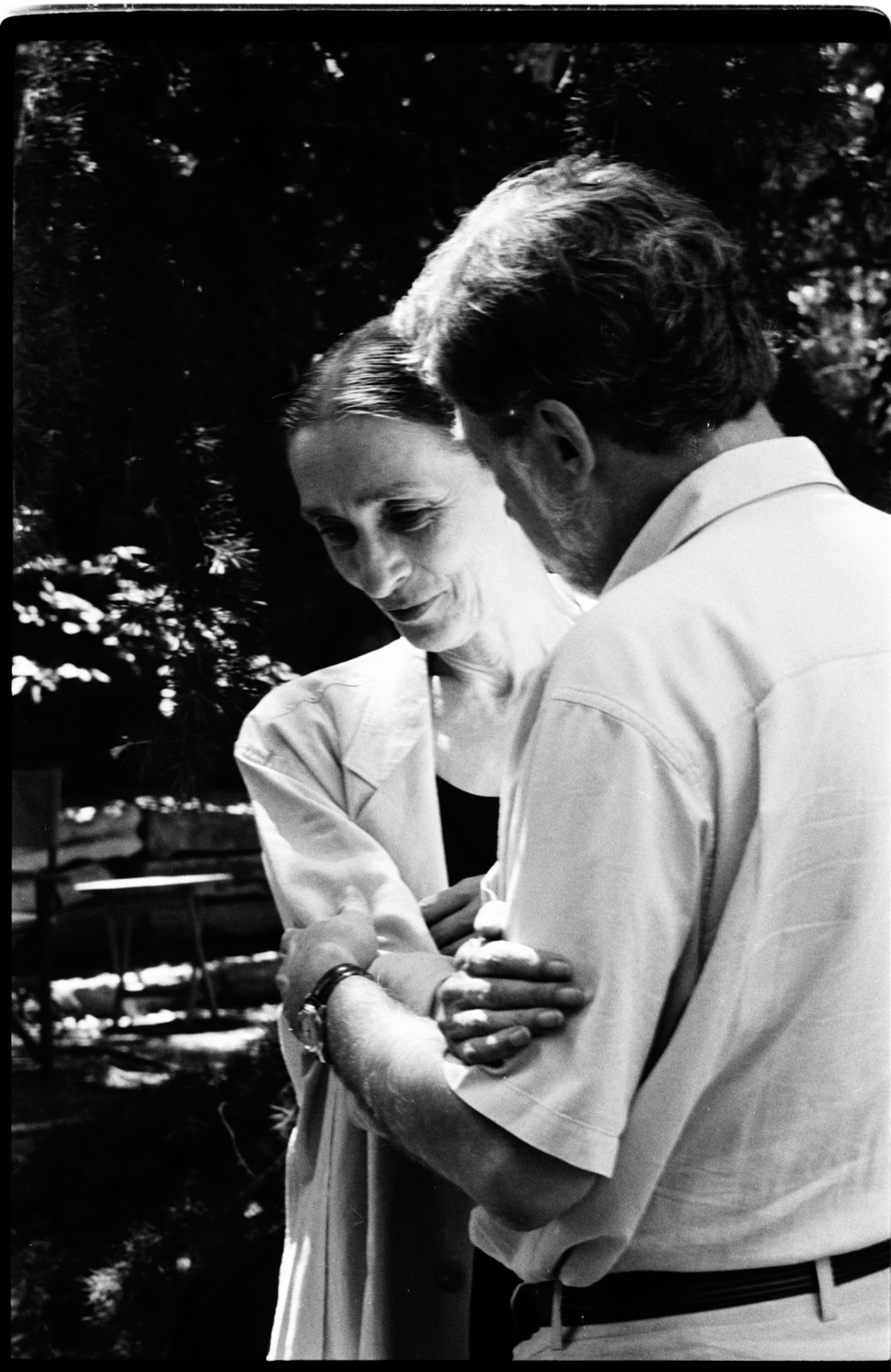

Pina Bausch and Bernard Faivre d'Acier in Avignon 2005 / Pina Bausch et Bernard Faivre d'Acier à Avignon en 2005

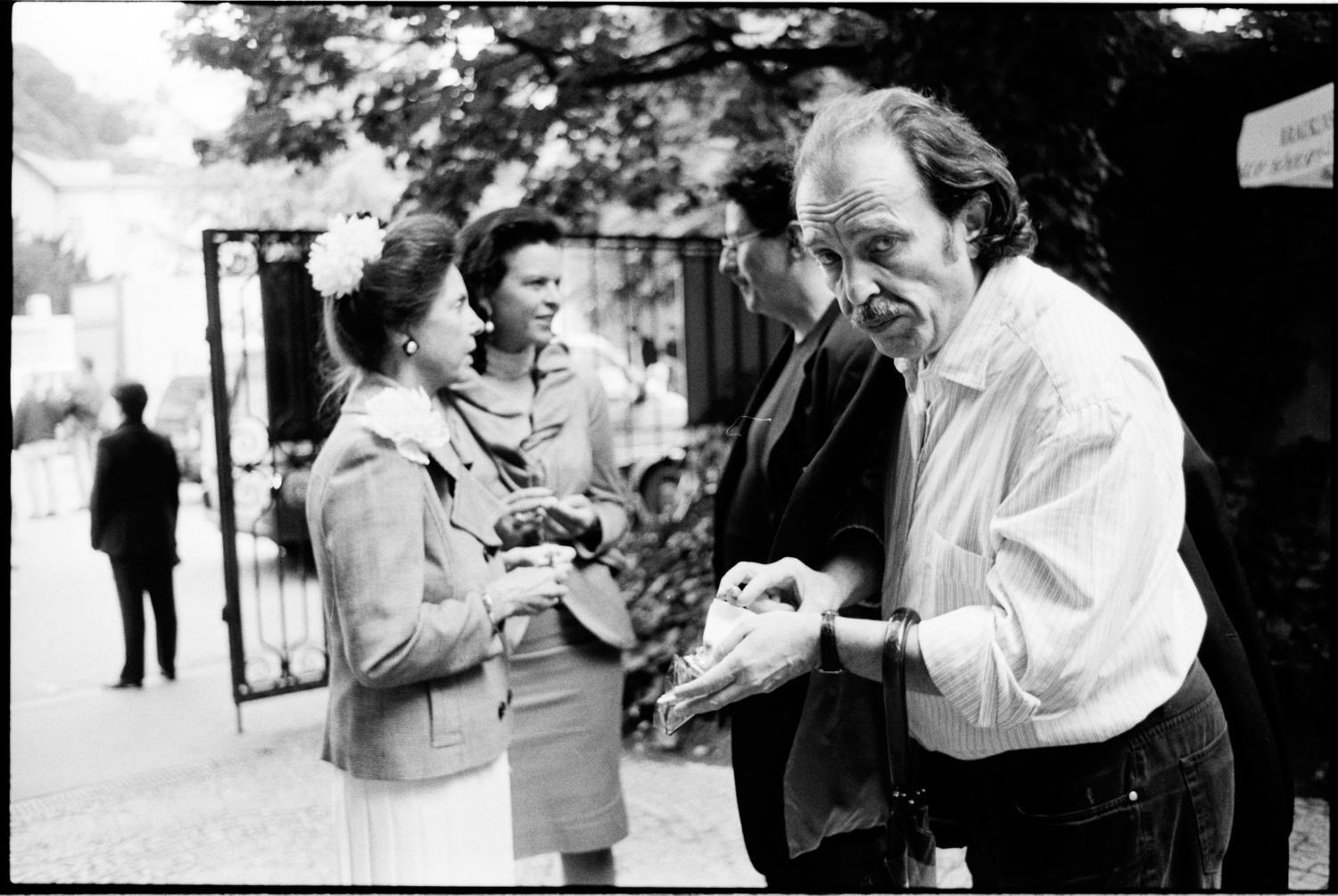

Franz West in Salzburg 2002/ Franz West à Salzbourg en 2002

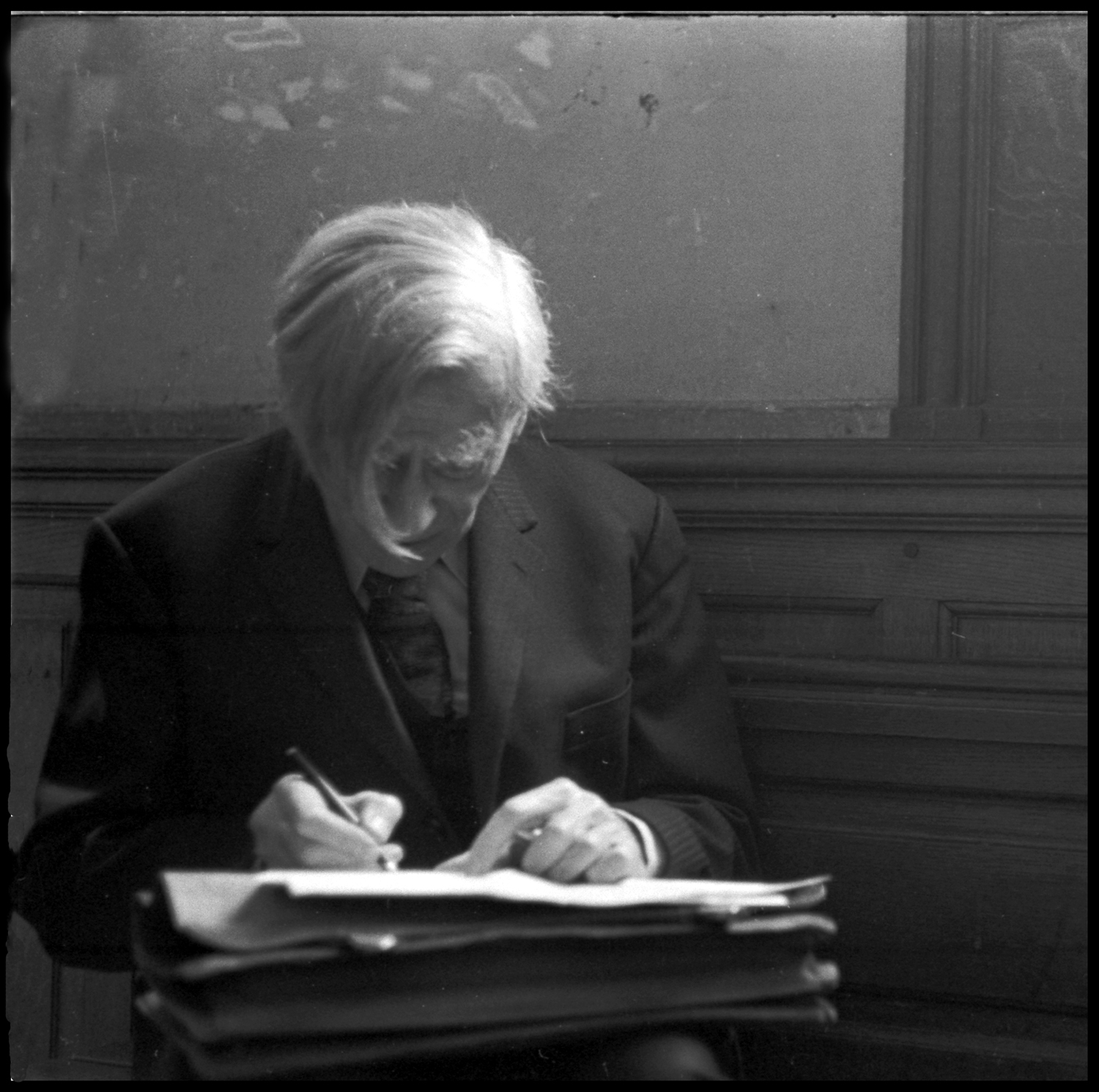

Vladimir Jankelevitch à Paris en 1976 / Vladimir Jankelevitch in Paris 1976

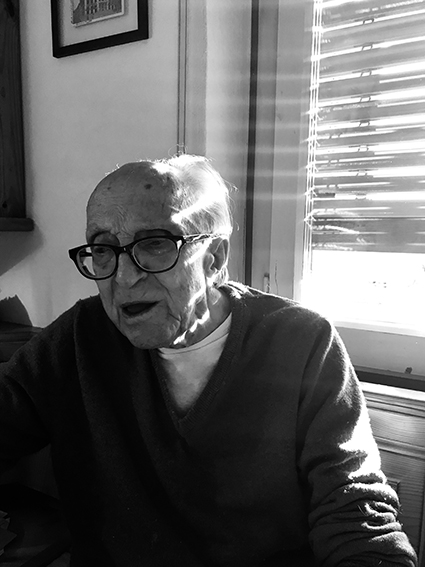

The writer Boris Pahor in his house in Triest 2018 / L'écrivain Boris Pahor chez lui à Trieste en 2018

Chinese filmmaker Wang Bing, Paris 2018/ Le cinéaste Wang Bing à Paris en 2018

Daido Moriyama in Paris 2018 / Daido Moriyama à Paris en 2018

Jean Pau Riopelle in Tanlay 1989 /Jean Paul Riopelle à Tanlay en 1989

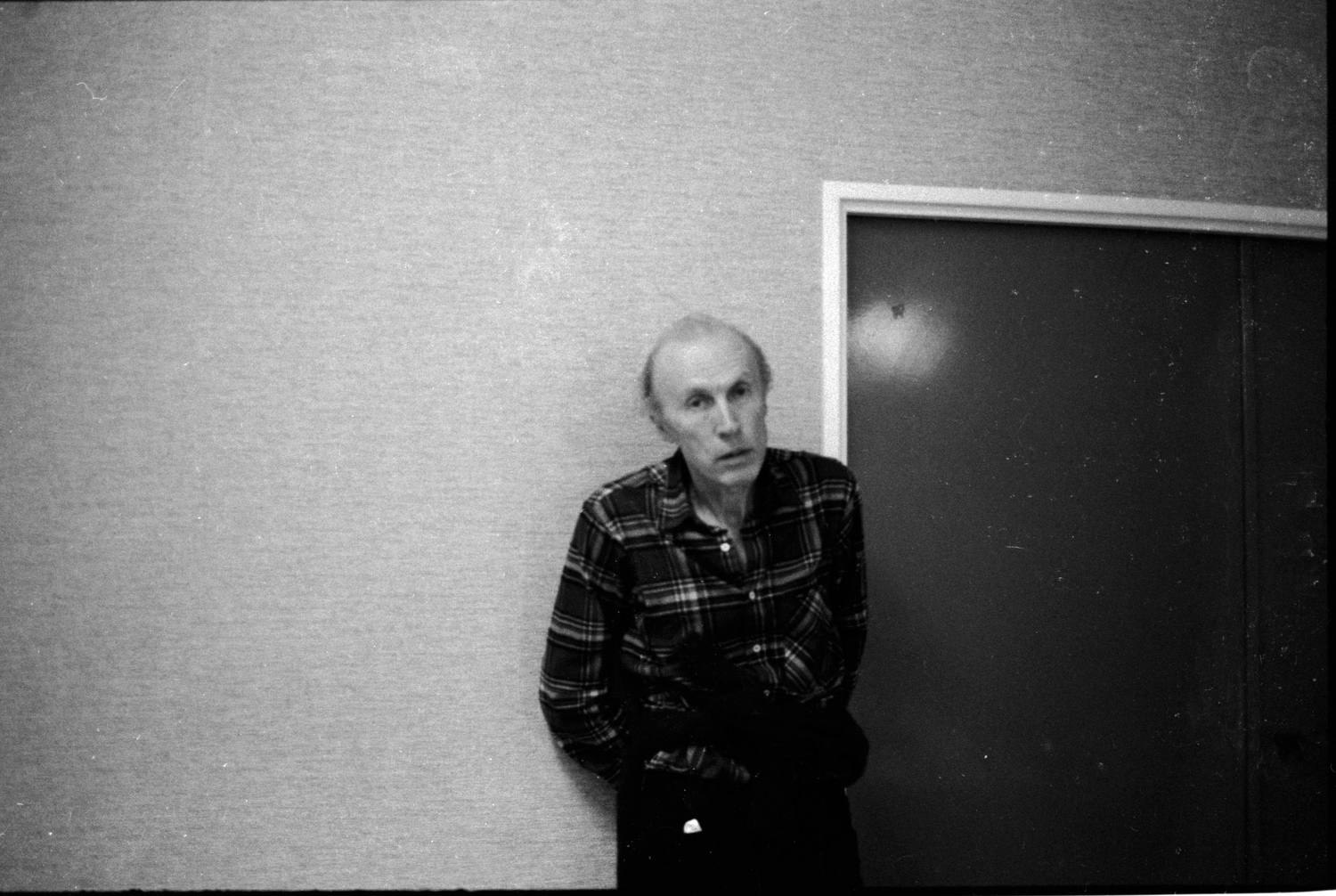

Tadeus Kantor Paris 1985

André Kertesz New York 1977

Dizzy Gillespie Théâtre des Champs Elysées 1977

eric rohmer paris 1979

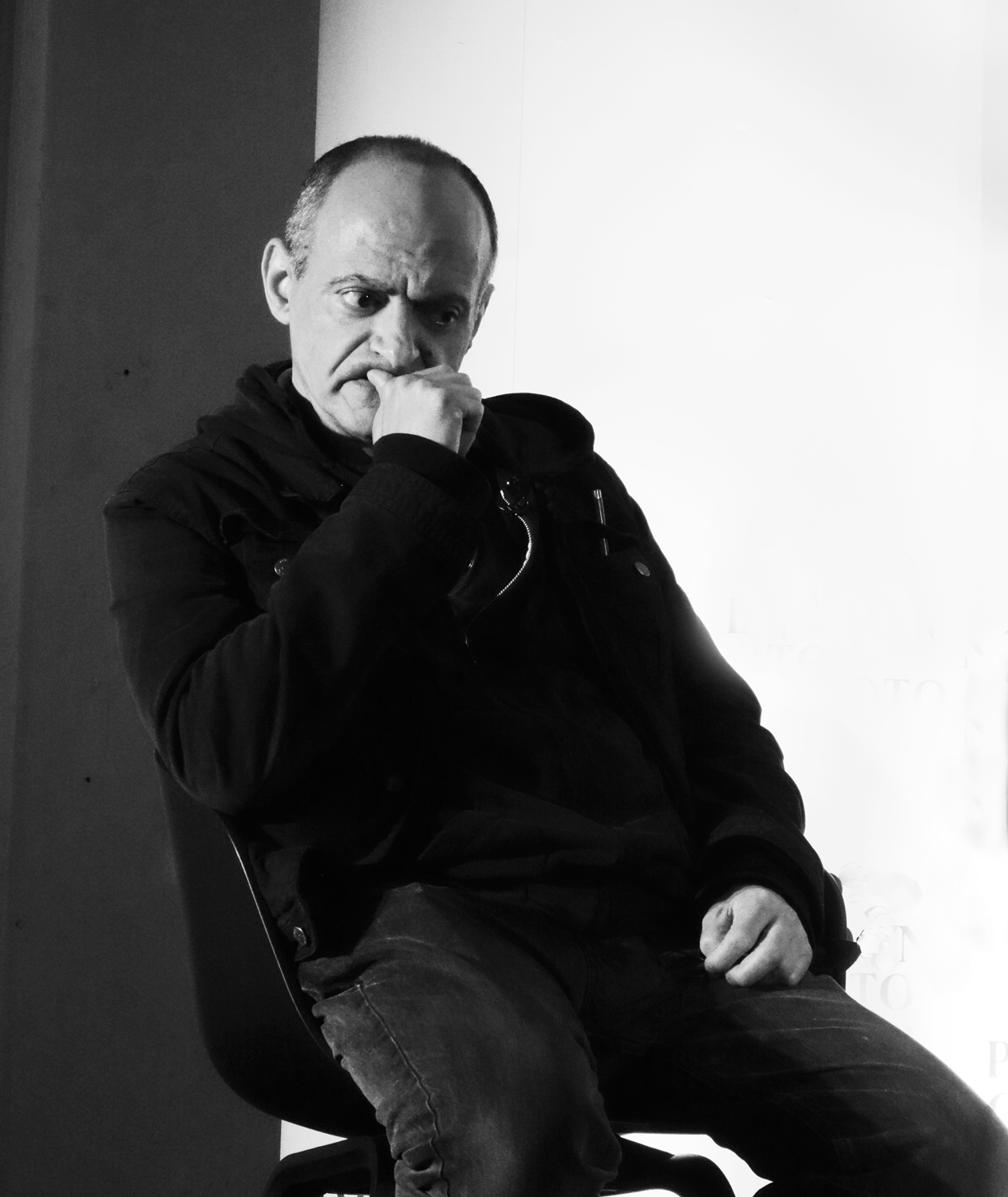

antoine d'agata London 2019

isamu noguchi new york 1978

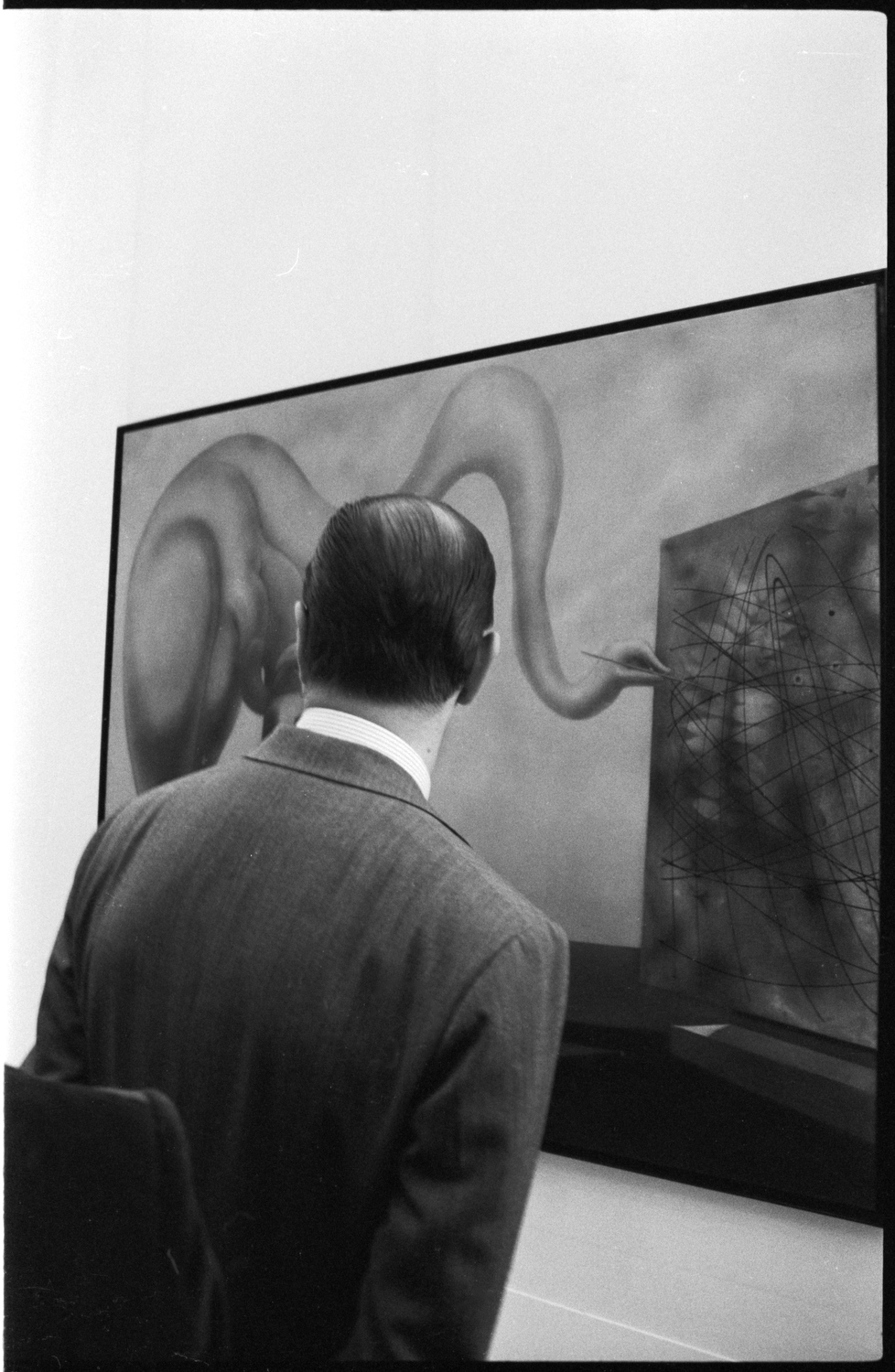

jacques chirac opening exhibition / vernissage paris 1975

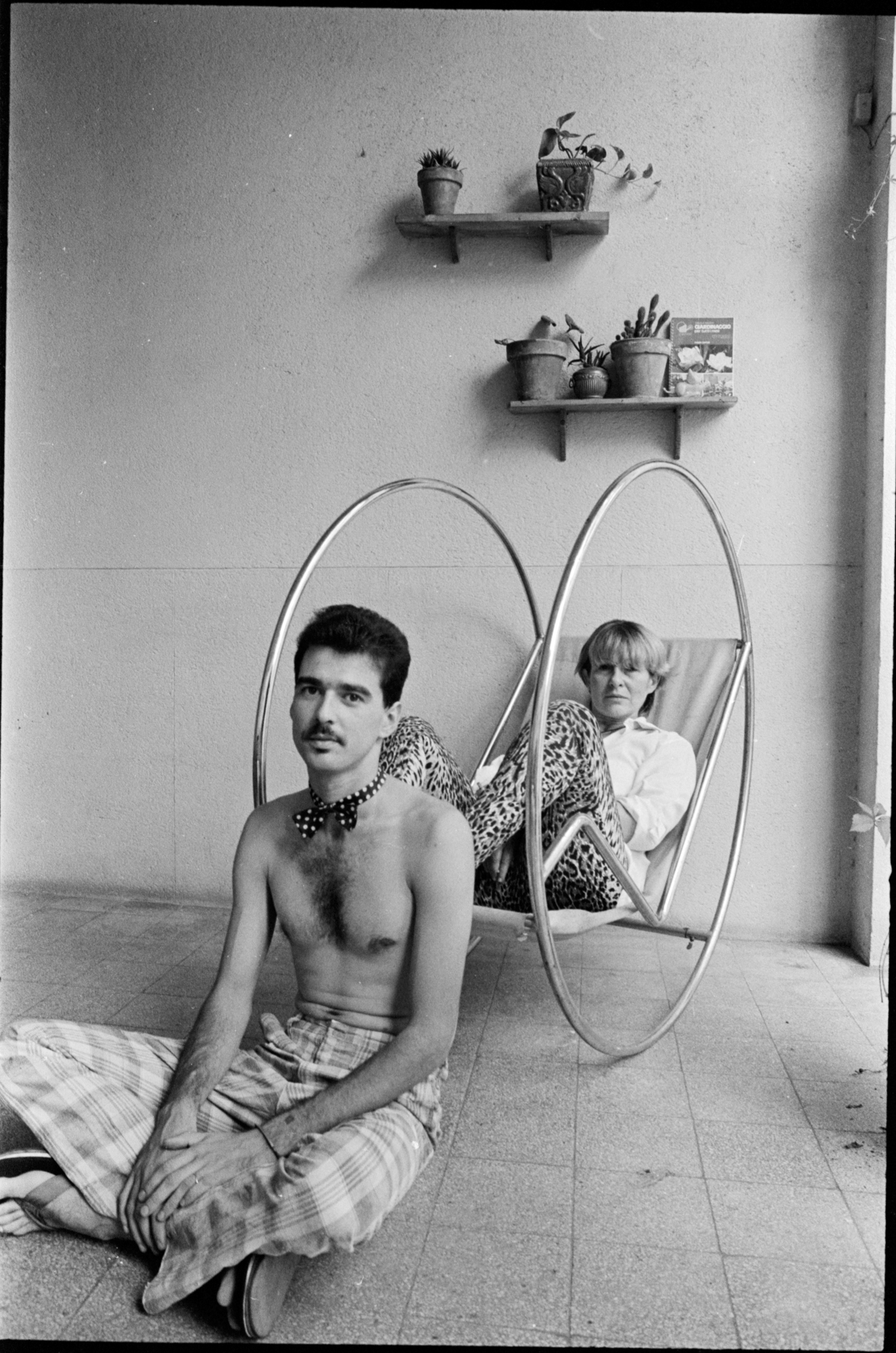

Letizia Battaglia and Franco Zecchin Palermo 1982

Christian Boltanski Paris 2020